Mind the gap — 50 years of shortening feedback loops

Published:

On the occasion of the 50th BATbern event, it occurred to me that it has been roughly 50 years since I started programming. In that time I’ve seen quite a few advances in Software Engineering. I’d like to take this opportunity to reflect on how these advances have not only shortened feedback loops in software development processes, but also how they have enabled new possibilities for innovation.

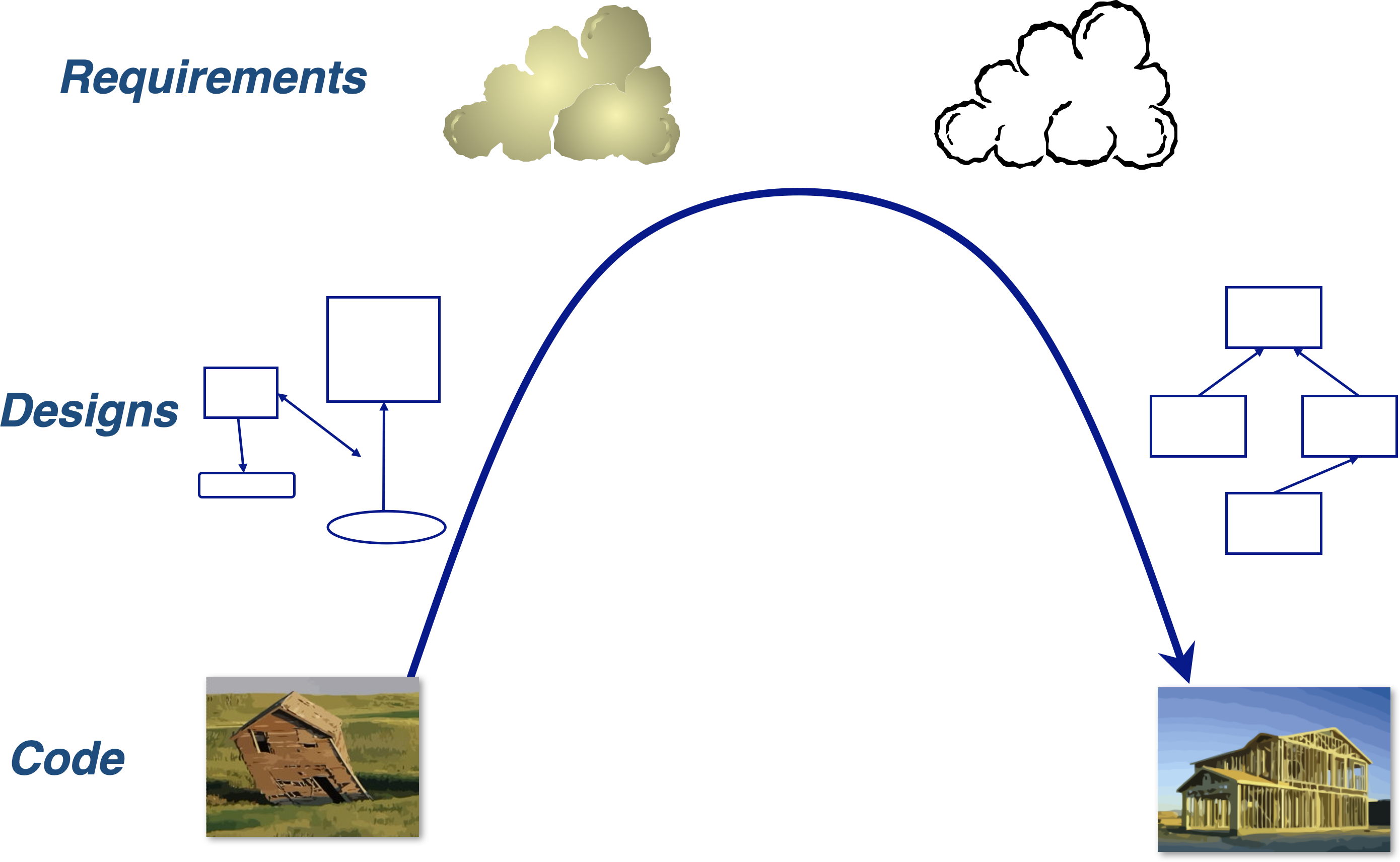

The execution gap

My first experience with gaps between expectations and reality in Software Engineering took place in 1972 when I started to learn to program. In this case the gap was simply the time between designing a program and actually seeing it run. I was a tenth-grade high-school student in Toronto when I was invited to the University of Waterloo for a week of Mathematics and a bit of programming.

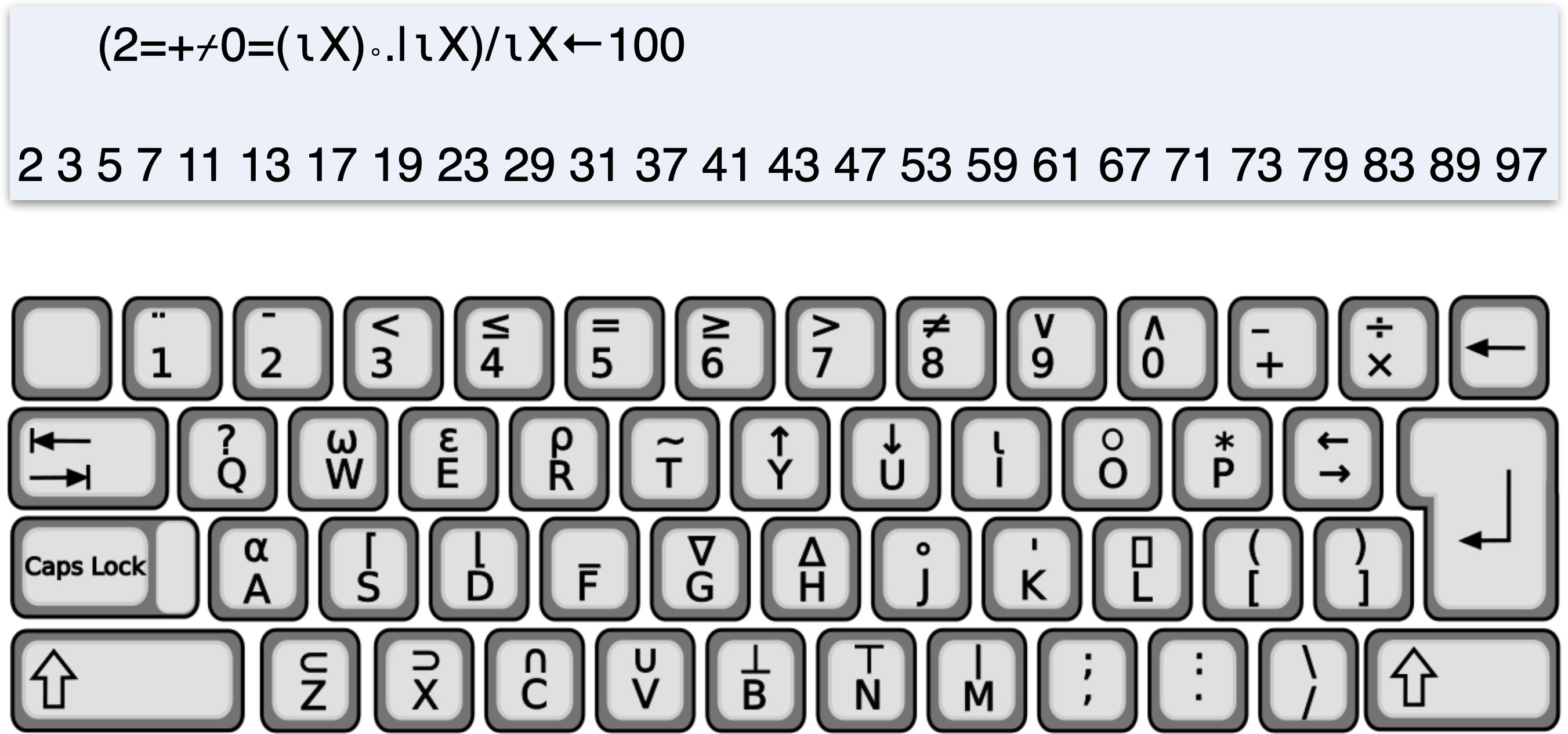

My first programming experience was with APL, a live programming language for manipulating matrices and arrays. We were taught by the amazing Prof. Lee J. Dickey, and we programmed interactively on a timesharing system, getting immediate feedback.

APL is facetiously known as a “write-only” language, due to its highly compact notation using Greek letters as array manipulation operators. Here we a see a one-line APL program to generate prime numbers. I remember writing a similar one-line APL prime sieve that looked something like this one.

[Sources: APL wiki, Wikimedia commons]

As an amusing parenthesis, I saw this sign displayed in the Open Air museum in Reykjavik in 2015. It looks fine, except the “typewriter” was not a typewriter at all.

|  |

|---|---|

| The typist at the kitchen table | IBM 2741 |

The so-called typewriter was actually an IBM 2741 used to program in APL. It is exactly the same kind of terminal I first used in 1972, including the APL typeball with Greek characters. I somehow doubt it was used to type letters in a kitchen in Iceland.

In the Autumn of 1972, the Toronto Board of Education introduced the first high school computer programming courses. We coded our programs with pencil on optical cards, like the one you see here.

We would hand our decks to the teacher, and get our printed output three days later. Debugging was not a pleasant experience. After my first experience with interactive APL, I felt I had moved back decades in time.

Later in the semester one of my classmates discovered that anyone at all could walk in off the street and use the keypunches and the high-speed job stream at the University of Toronto. After that we did all our homework at UofT.

Closing the execution gap

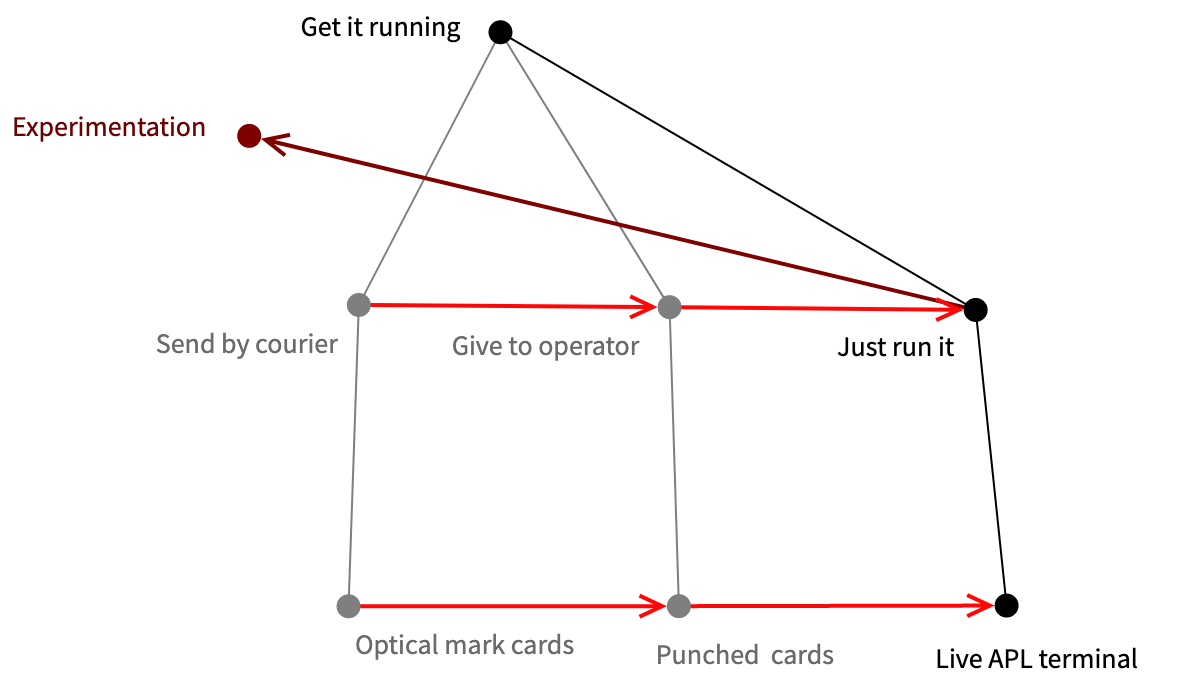

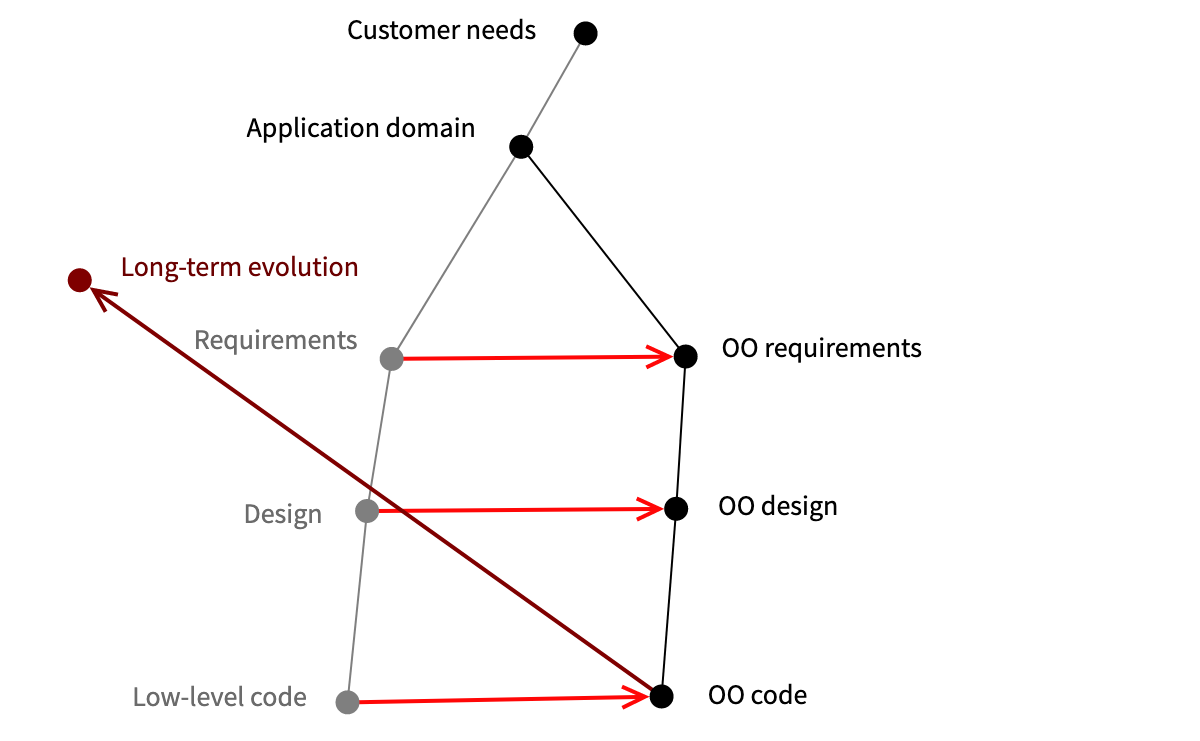

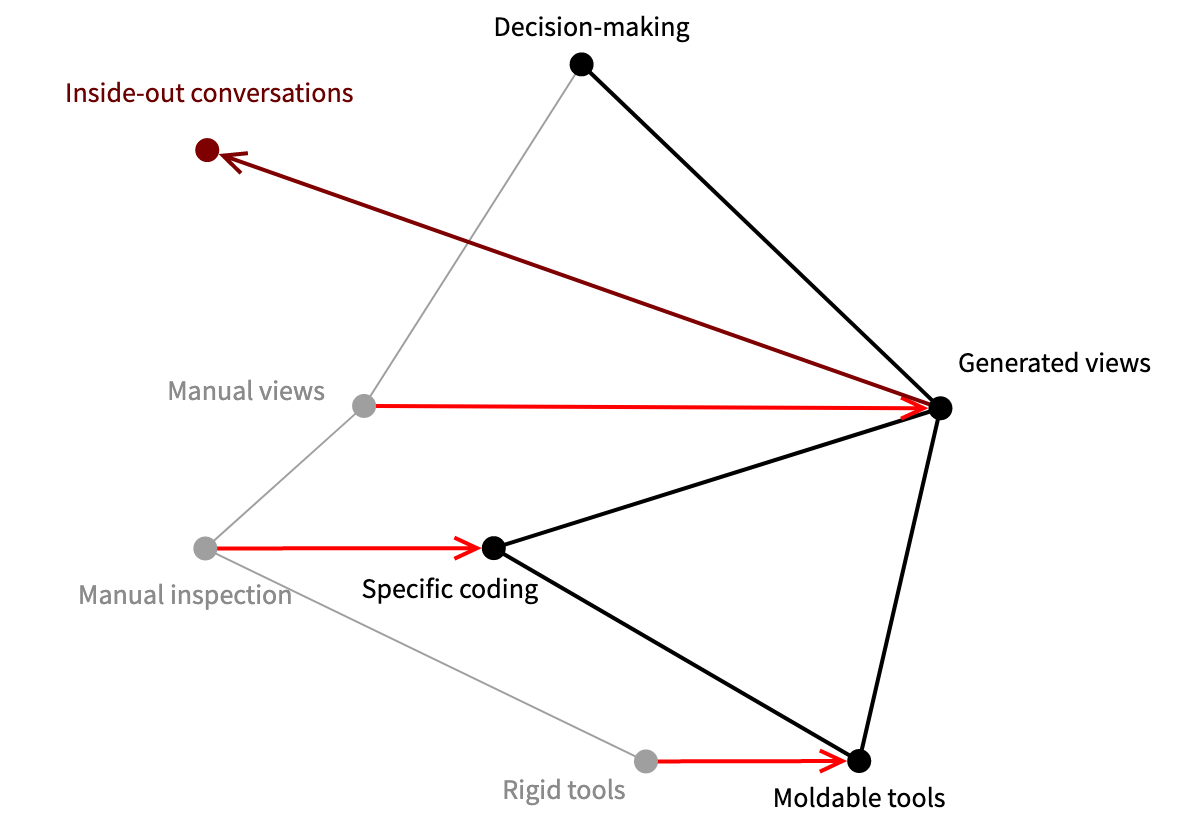

Here we see a “Wardley map”, a diagram for business strategy that maps components with respect to user need.

At the top we see the need for getting our programs running. The other nodes are components that contribute to that need. From bottom to top components provide more value to the user, and from left to right they evolve from genesis, through prototypes, to products, and all the way to commodities.

The grey lines show which components contribute to others higher up. So, optical mark cards are sent by courier and contribute to getting the code running. The red arrows indicate evolution of components towards products and commodities. Greyed-out components are those from the past. The dark red arrows point to new components that emerge from the evolution.

In this case we see that the source code medium evolves from optical mark cards via punch cards to interactive terminals, shortening the feedback loop. Similarly, getting the program to run evolves from sending it by courier to just hitting the “enter” key.

What’s interesting, however, is that when the technology is sufficiently evolved, new opportunities arise that could not be imagined before. In this case, since the feedback loop is so short with live programming, we can experiment in ways that were not possible before. Since this form of experimentation is a new thing, it appears towards the left of the map, so can also be expected to evolve.

The modeling gap

After high school, I studied Mathematics at Waterloo, and later switched to do a Masters and PhD in Computer Science at UofT. There I experienced the enormous gap between conceptual models and implementation.

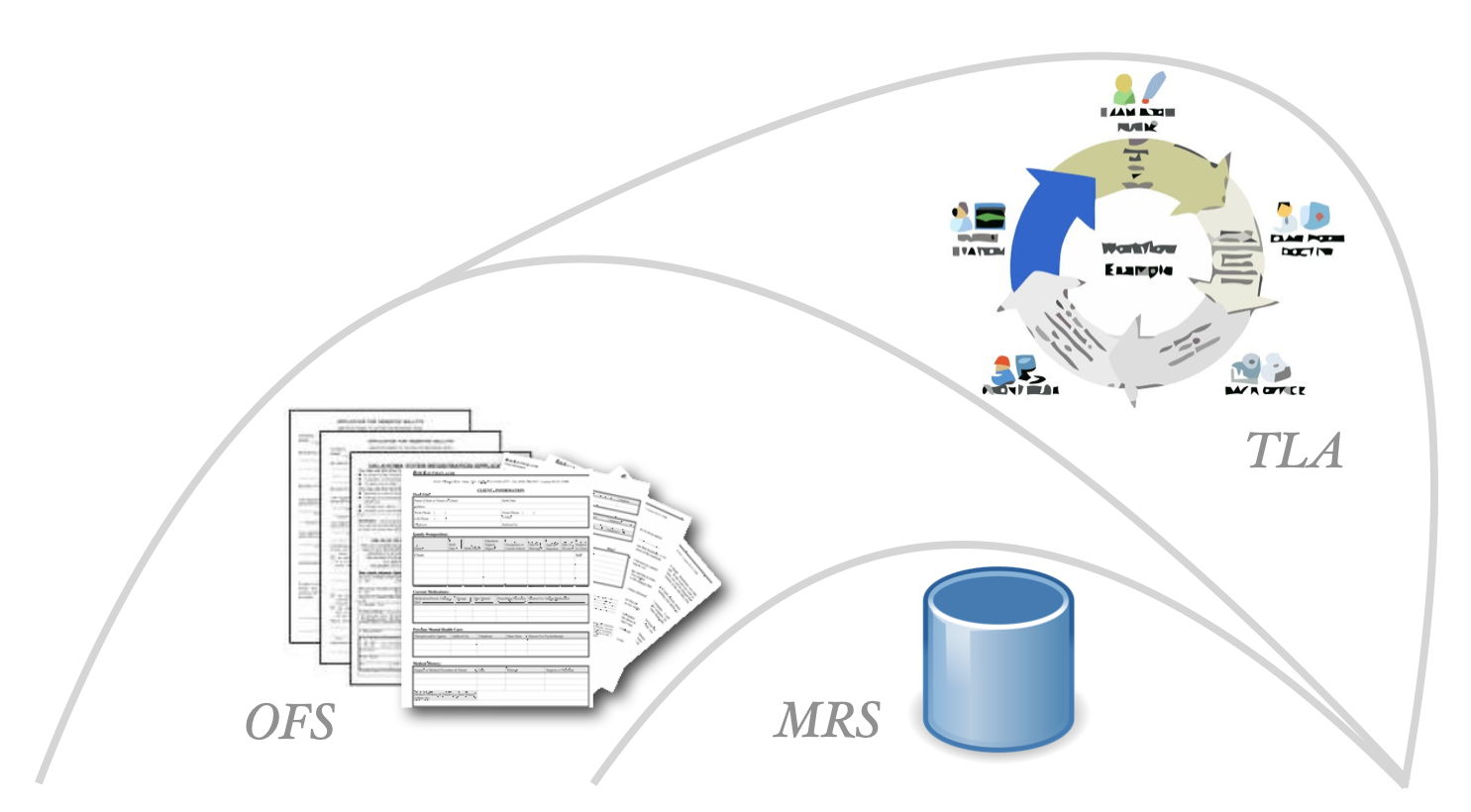

The task for my MSc thesis was, together with another Masters student, to build a workflow system, called TLA, on top of another prototype of an electronic Office Forms System. OFS was itself built as a layer on top of MRS, the Micro-Relational System, one of the first implementations of a relation database management system for Unix.

I was very excited about the project, and had a clear idea of what to do, before even looking at the code. When I opened the box, however, I had trouble mapping the concepts to the C code. Essentially the problem was that I was looking for the domain concepts in the code, but I could not find the objects.

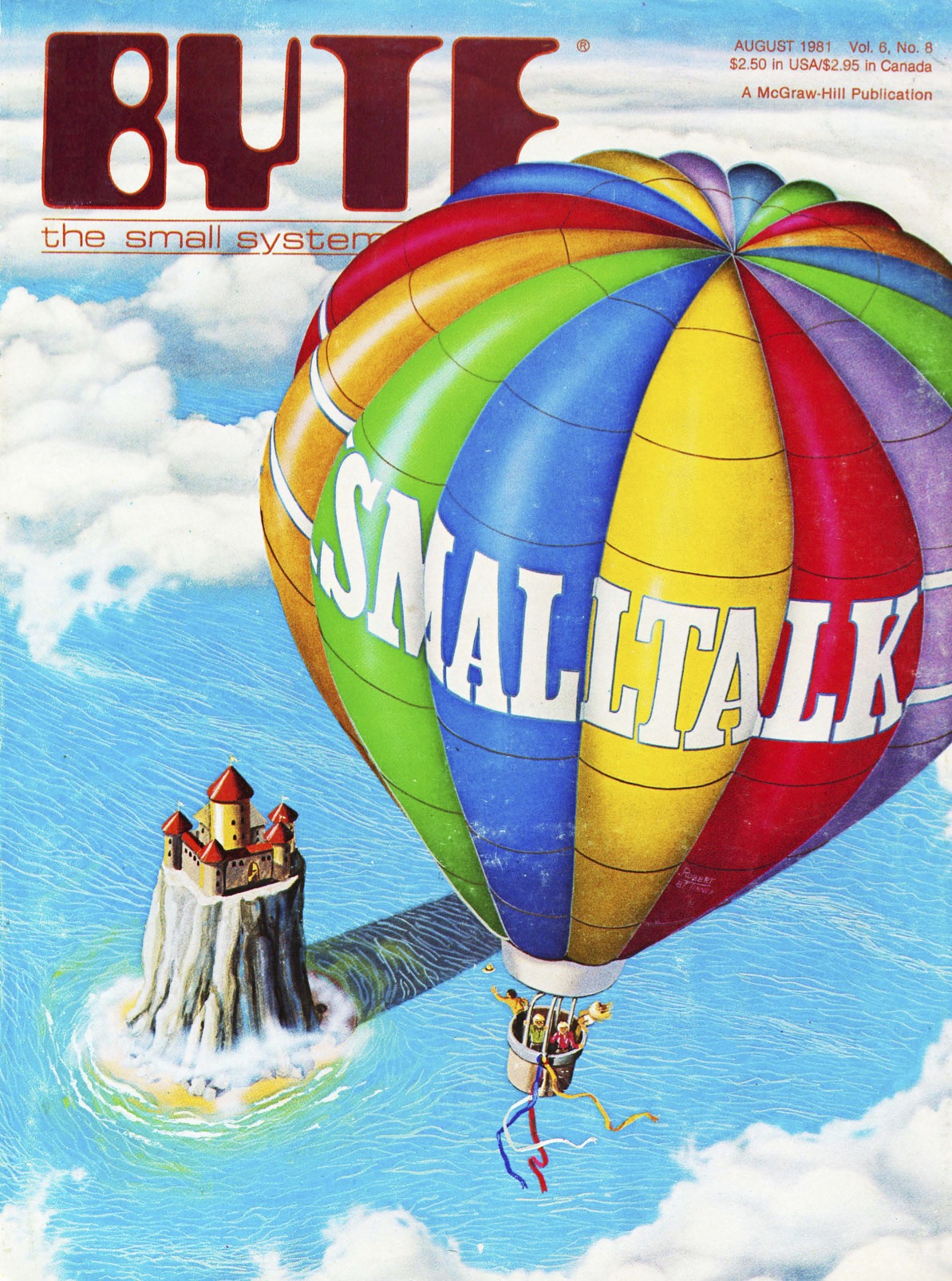

I then had an epiphany when I saw the August 1981 special issue of Byte magazine dedicated to Smalltalk, a brand-new object-oriented language and system. This was exactly what I was looking for!

|  |

|---|---|

| August 1981 Byte special issue on Smalltalk | Introducing the Smalltalk-80 System |

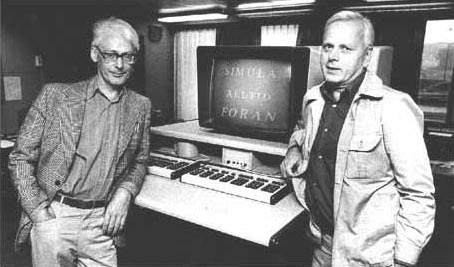

Object-oriented programming was born in Norway in 1962, where Ole-Johan Dahl and Kristen Nygaard struggled to implement simulation software using ALGOL, an early procedural language.

[Source: Journal of Object Technology]

They invented objects, classes and inheritance to model real-world simulations as a thin layer on top of ALGOL. The resulting language was called Simula, which was standardized in 1967. Roughly 20 years later Bjarne Stroustrup, an experienced Simula programmer, started adding a similar thin layer to C, called “C with Classes”, and later renamed “C++”.

Also during the 1960s, an American computer scientist, Alan Kay, noticed that computer hardware was getting smaller and faster at an astonishing rate. He predicted that, somewhere down the line, you would be able to hold a computer in your hand, providing access to an encyclopedia of multimedia data. He figured that it would only be possible to build the software for such a so-called “Dynabook” using a fully object-oriented language and system. He convinced Xerox PARC to fund the development of not just the language, but the entire system down to the metal. The Smalltalk team indeed built not only the Smalltalk language and VM technology, but also the first graphical workstations and windowing systems.

I read about this and proposed to my supervisor at UofT, Prof. Dennis Tsichritzis, that to build our advanced electronic office systems we needed an object-oriented language and system. Since Smalltalk wasn’t available for our hardware, we started research into building our own language and system. Dennis told me, “Grab a couple of MSc students and go implement an object-oriented system.” It was not that easy, but we did manage to come up with something interesting.

Closing the modeling gap

Object-oriented programming made it possible to trace concepts from requirements through design down to implementation. This certainly made it easier to develop software systems, but what is interesting is that this enabled long-term growth. Not only development, but maintenance and evolution of such systems was facilitated by making it easier to navigate from requirements to code.

The productivity gap

Whereas in the 1980s most of the resistance to OO technology came from concerns about performance (after all, every message to an object entails at least one additional indirection), by the 1990s machines were fast enough that developer productivity was seen as being more important. But what is “productivity”?

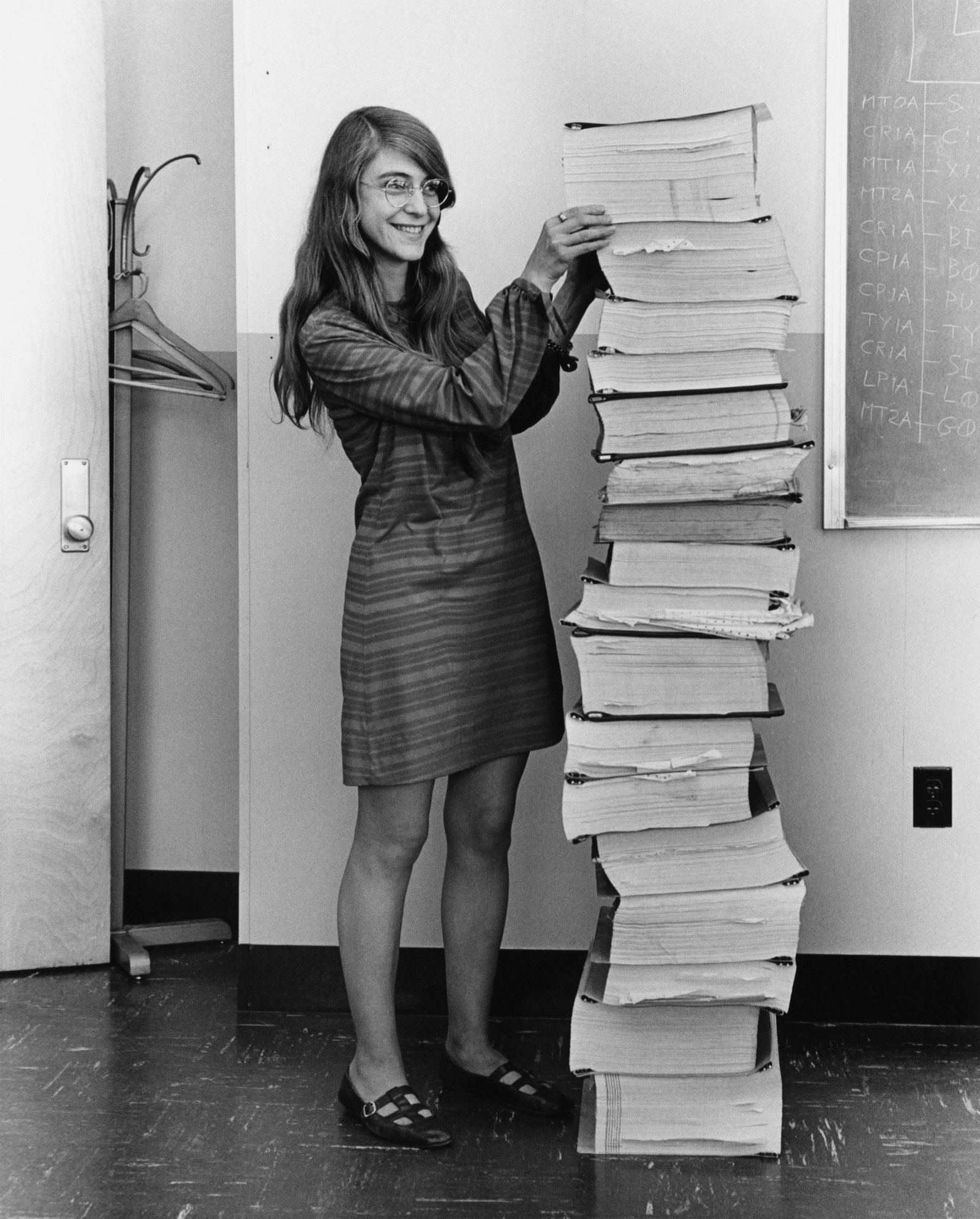

This great photo shows Margaret Hamilton, NASA’s lead software engineer for the Apollo Program, standing next to printouts of all the code produced by her team for the 1969 moon landing.

[Source: Wikipedia commons]

But software productivity clearly isn’t just producing more code in the same amount of time, otherwise refactoring would be seen as negative productivity! The trick is to produce more value for the customer, whether this is more code or less.

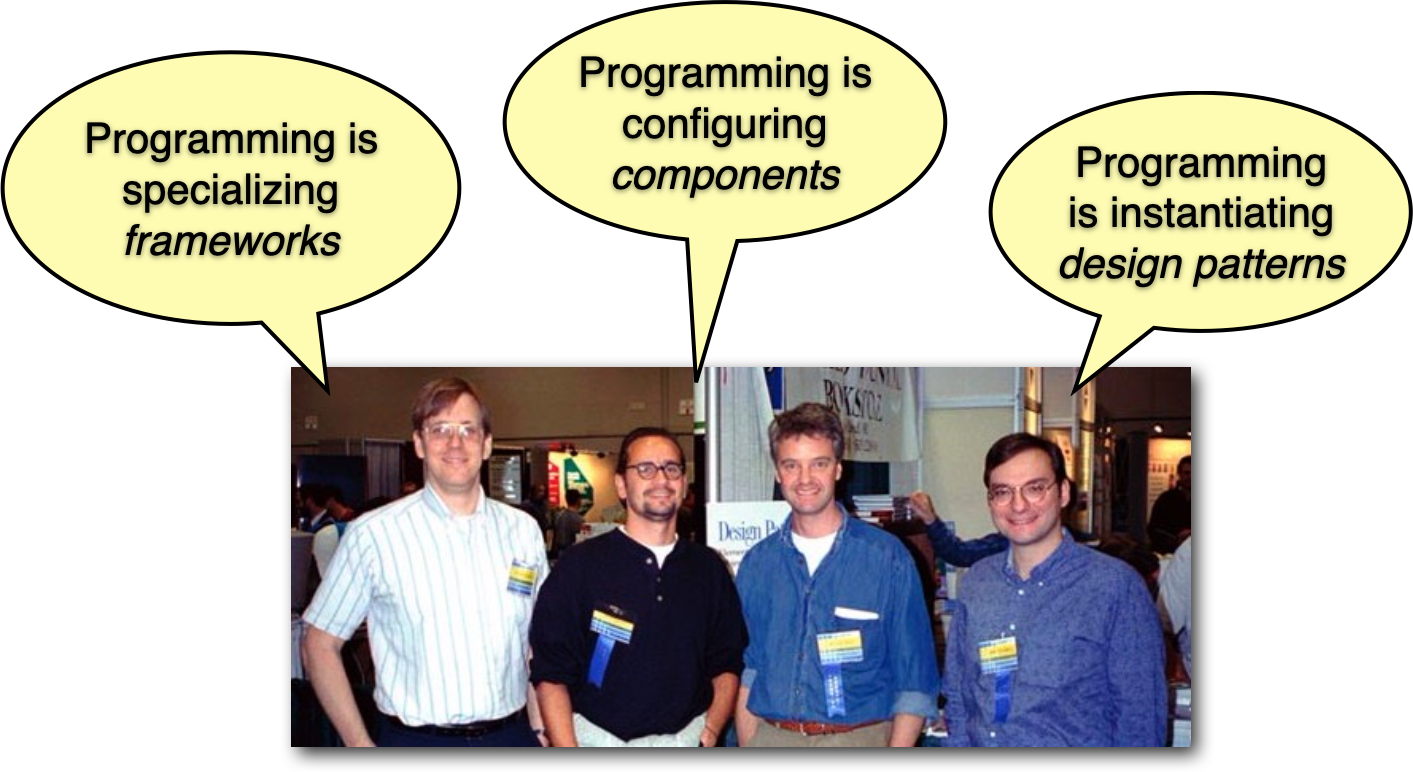

In the 1990s, the mantra was “Objects are not enough”. But if so, what else was needed? This photo shows Ralph Johnson, Erich Gamma, Richard Helm and John Vlissides, the “Gang of Four” who produced the first “Design Patterns” book. All four were also experienced in developing object-oriented frameworks based on reusable architectures and software components. They noticed that the same design ideas appeared in all the systems they had developed independently, and figured something interesting was going on.

[Source: Medium]

Object-oriented programming was so successful that, by the mid 1990s, there were already many, very large OO systems. Despite the increased ease of evolution, many of these older OO systems started to show the typical symptoms of legacy systems predicted by Lehman and Belady’s laws of software evolution.

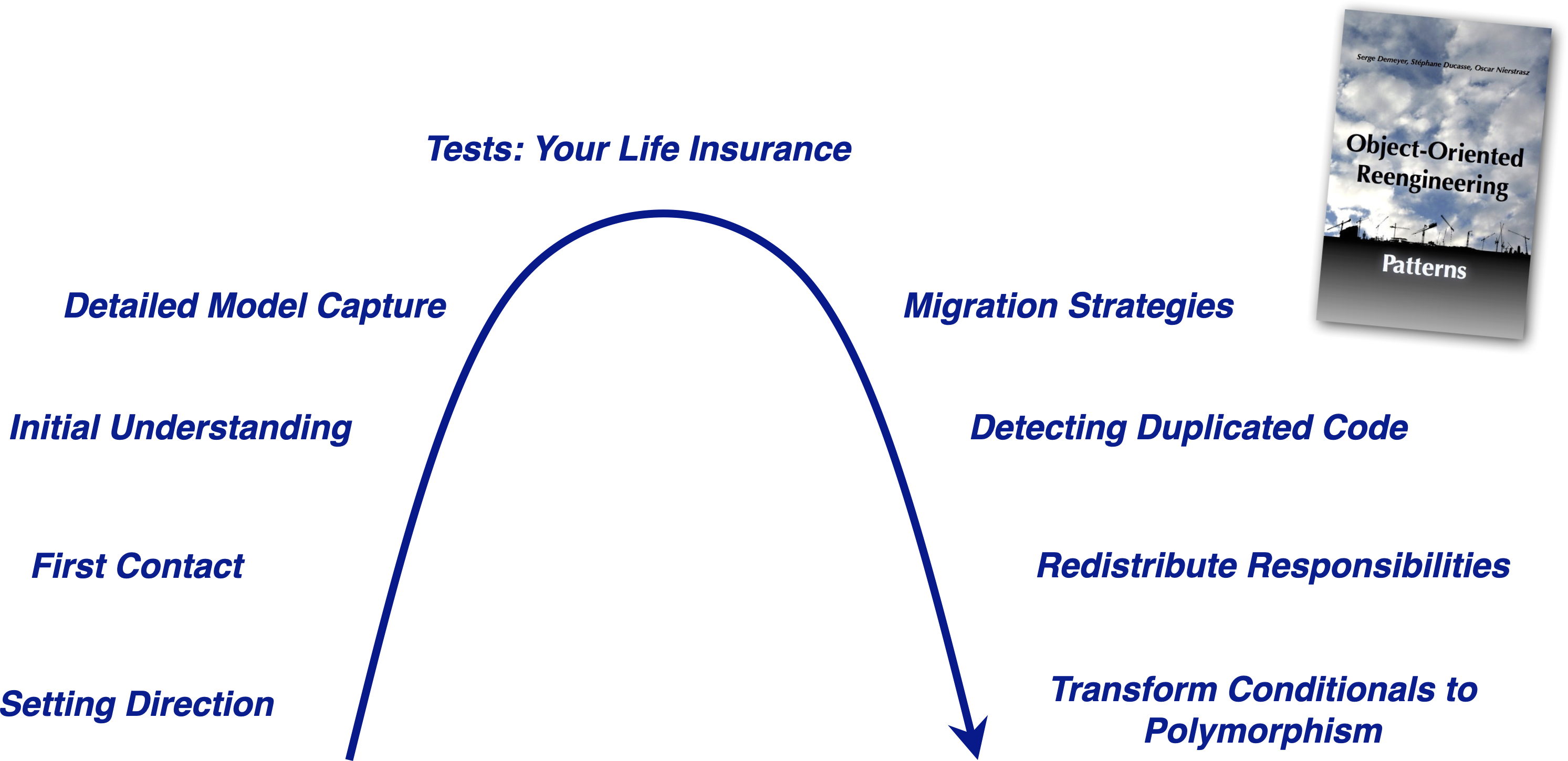

We started a European project called FAMOOS in 1996 with industrial partners Nokia and Daimler-Benz to reengineer legacy OO software towards cleaner, more scalable component-based frameworks.

Our strategy was to recover lost design knowledge by reverse engineering and analyzing the legacy software, and then migrating it step-by-step towards a newer and cleaner architecture.

In the process of analyzing dozens of diverse OO software systems at Daimler and Nokia, we discovered numerous reverse and reengineering patterns that could be applied in multiple contexts. For example, the pattern Interview during demo helps a stakeholder you are interviewing to focus attention on concrete features and usage scenarios as you are trying to gain an initial understanding of a software system. This is far more effective than watching a slideshow or scribbling on a whiteboard. One of the key outcomes of this work was the open-source book, Object-Oriented Reengineering Patterns.

Closing the productivity gap

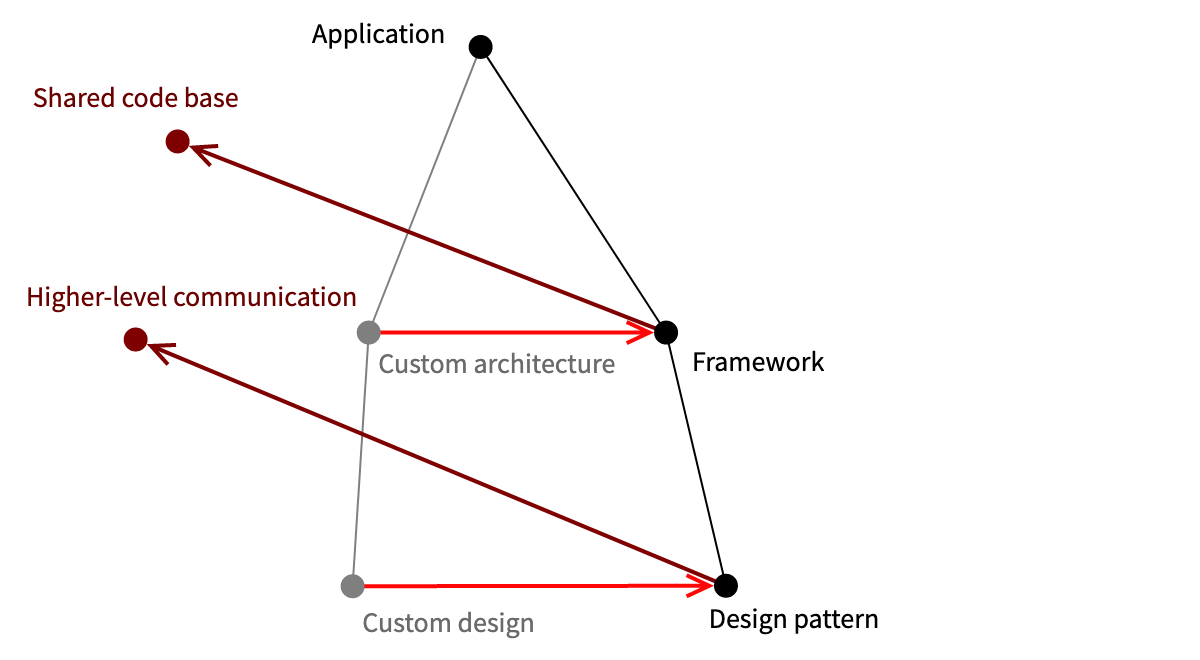

Design patterns are valuable not only as a way to teach software developers about best practices, but they also offer a way to raise conversations about design to higher levels. If I say to you, “Do we need a Singleton here?”, you should immediately understand what’s at stake.

Frameworks and components also raise the level of conversation. Instead of dealing with many unconnected applications, we deal with a Software Product Line of applications sharing a common code base.

The testing gap

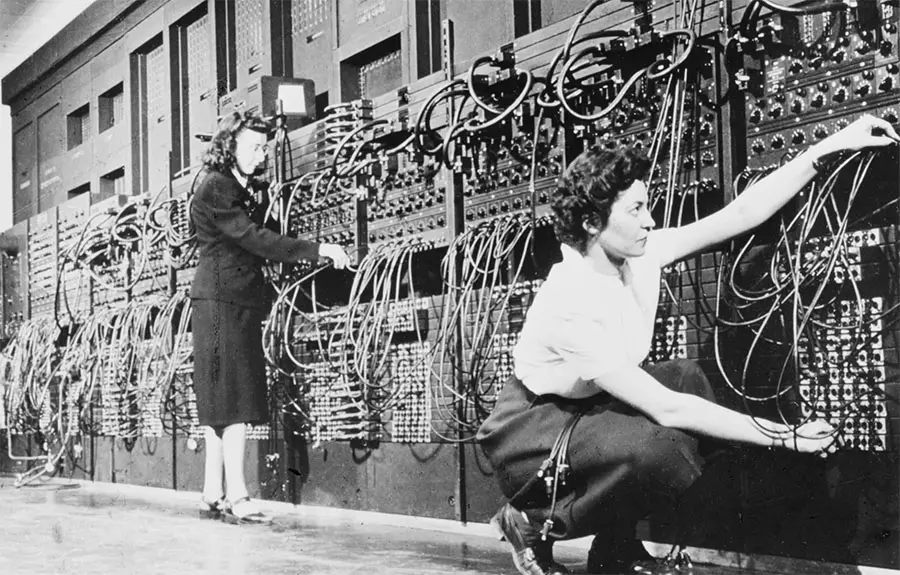

Once upon a time (and also today), testing was a manual process.

This great photo shows the ENIAC, one of the very first digital computers, completed in 1945. As you can imagine, testing was a slow, laborious process of rewiring. Before automation, manual testing of software systems could be as painful as rewiring the ENIAC.

[Source: National Archives]

Automated testing only started to become popular with the introduction of Kent Beck’s SUnit framework for Smalltalk, and the subsequent port of SUnit by Kent and Erich Gamma to Java.

During the FAMOOS project we were concerned about a particular project we were analyzing, and for which we could find no test cases. When we asked, we were told, “Oh, but we have very extensive test cases!” “Great!” we said, “Can we see them?” They then brought us a big book of test cases that some poor person had to manually step through every time the tests were run.

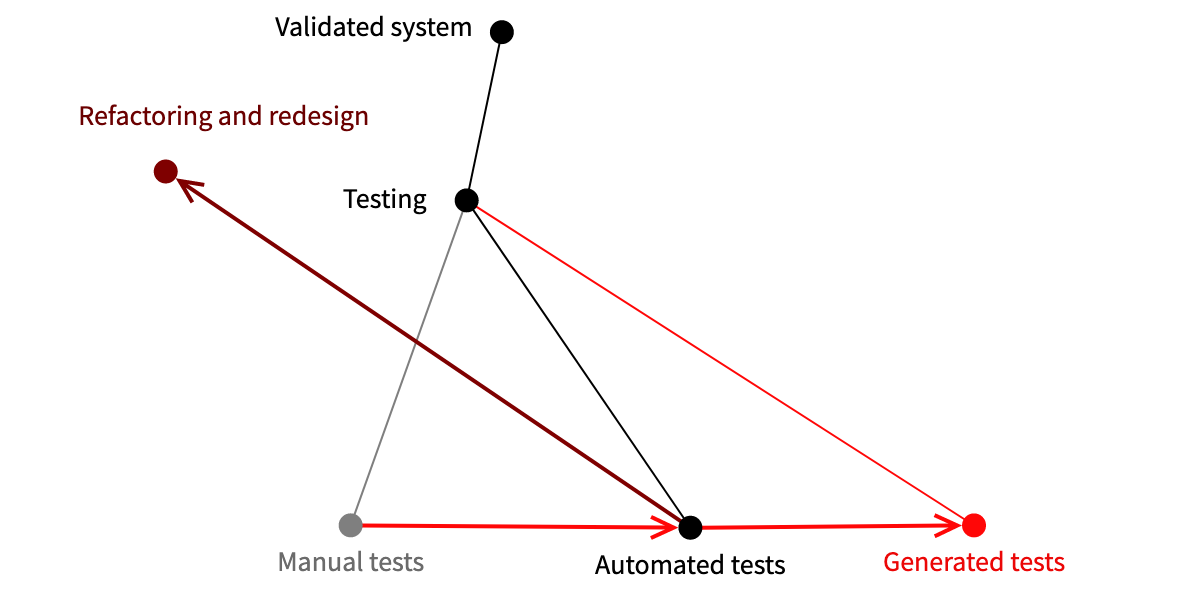

Closing the testing gap

The transition from manual to automated testing not only shortened the feedback loop from coding to validating that predefined test cases would pass, but it enabled something new.

With high test coverage, it was now possible to introduce radical changes to the design of a software system, and to subsequently ensure that everything that worked before was still working. The obvious downside was the need to manually write the test cases. In any case, you only had to write an automated test once, whereas a manual test had to be evaluated each time by hand.

The open question is where we can go with generated tests. So far these mostly just identify cases where the system fails, but there are some exceptions. For example, property-based testing can test business logic. When generated tests are ready to replace manually-written tests, there will certainly be new opportunities that can be hard to imagine now.

The deployment gap

Although there were many other exciting advances in the 1990s, let us skip ahead.

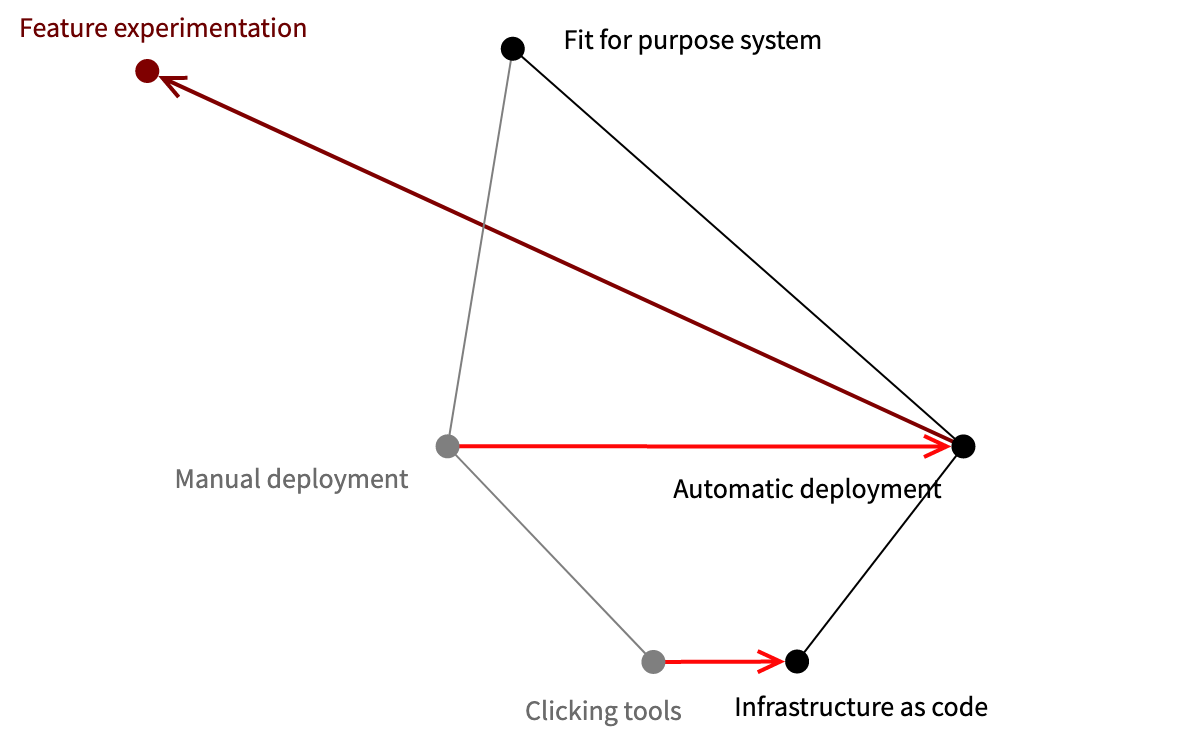

Earlier we saw the “execution gap” between design and execution of a running program. The deployment gap concerns the gap between having a running and validated system and deploying it with end users. Until the introduction of DevOps, this could be a slow and painful manual process.

Closing the deployment gap

Although DevOps clearly served to automate and close the gap between development and deployment, what is interesting is the new opportunities it created.

In particular, with DevOps it is possible to experimentally introduce new features for selected groups of users to monitor and assess their impact on business. Without DevOps, the very idea is laughable.

The sustainability gap

Let us move to the present day. We know that unfettered growth of software systems leads to legacy issues. Very large software systems don’t scale well for decision making because we don’t, and can’t, understand them. Let’s take a look for some of the reasons.

Mainstream IDEs are glorified text editors

All mainstream IDEs are pretty much the same: they focus on editing source code.

Why is this a problem? First of all, putting a text editor at the center of the IDE presupposes that you are generally either reading or writing code. But in fact we only spend a small part of our time writing code.

Reading code does not scale

On the other hand, reading code for very large systems does not scale. You simply cannot read hundreds of thousands of lines of code, let alone many millions of LOC.

Lightweight tools are more effective than reading code

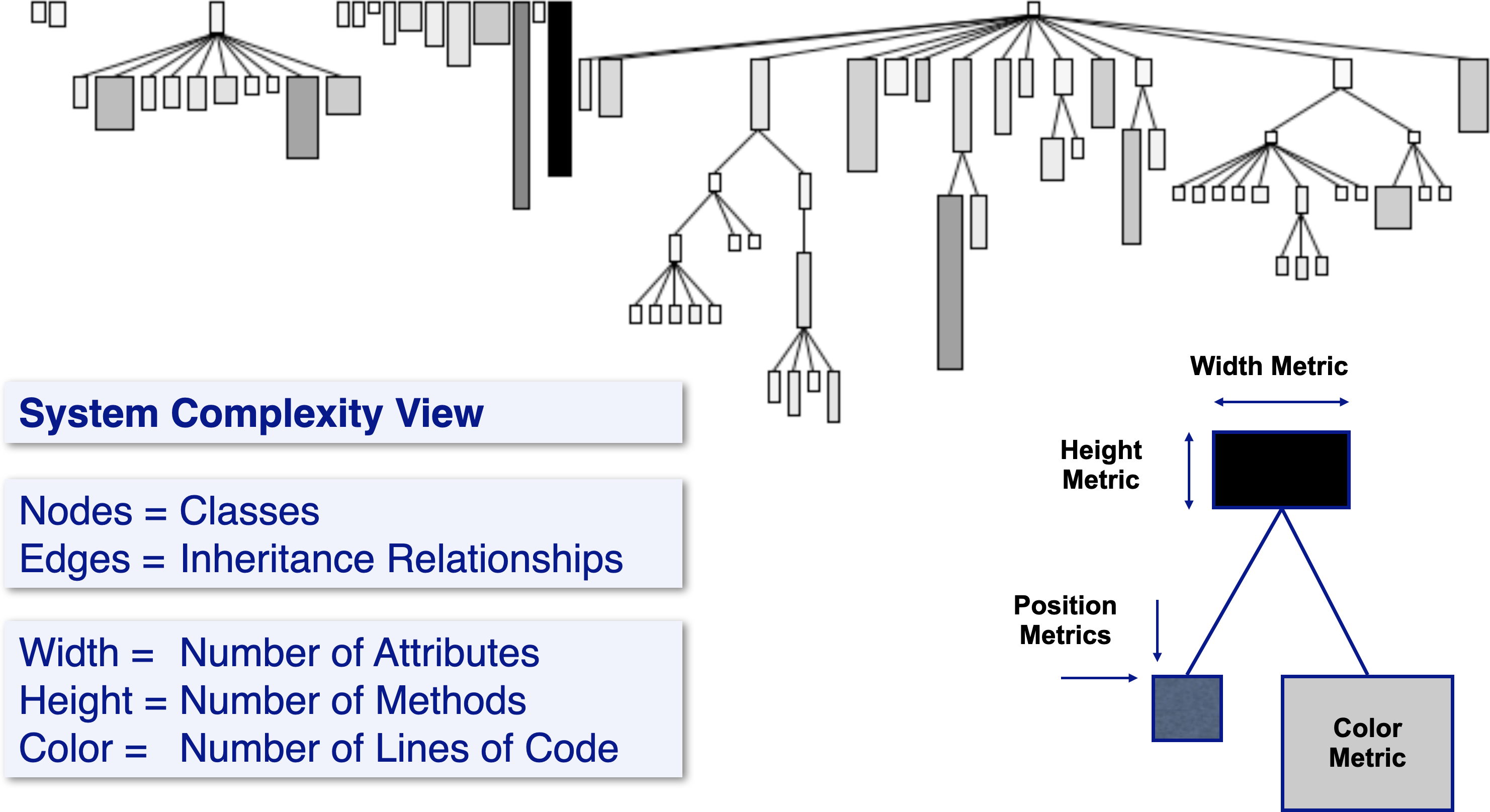

One of the key reengineering patterns is Study the Exceptional Entities, which helps you to learn quickly about potential problems in a software system by asking questions about outliers, such as very large classes, or classes with many fields but little behavior. Lightweight tools and metrics can help you to gain insight into a complex system.

In this system complexity view, we map the numbers of attributes, methods and lines of codes to the width, height and color of classes in a hierarchy. This immediately highlights classes with abnormally many lines of code, or lots of data with little behavior.

While such tools are useful early when investigating a system, they are still generic. To support solving concrete problems, tools have to take the context of those problems into account. The key question is whether such tools can be cheaply produced to answer specific questions about a given software system.

Code is disconnected from the running application

There is a huge gap between software source code and a running application. In a classical development environment you stare at source code, modify it, then run the code to see the effect in the running application. When that fails, you go back to staring at the code.

Perhaps you will have a test case or a breakpoint that will land you in a debugger to explore the live object, but from there you can only go back to playing with the source code. Worse, if you start from the running application, you may struggle to answer questions such as, “Where is this feature implemented?”

Q&A tools lack context, so give unreliable results

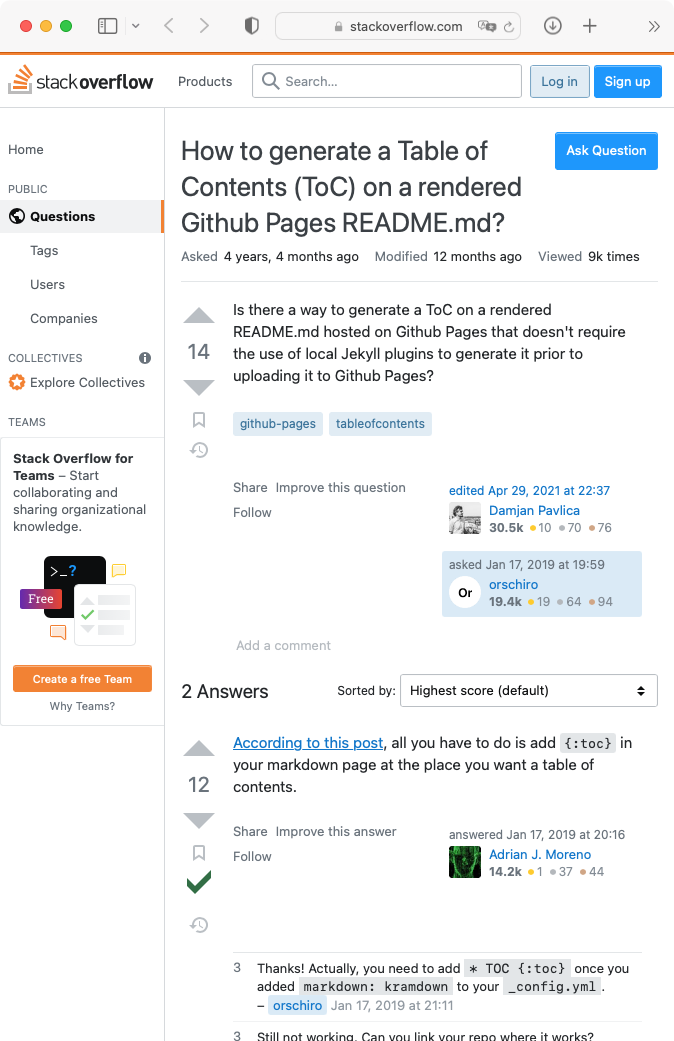

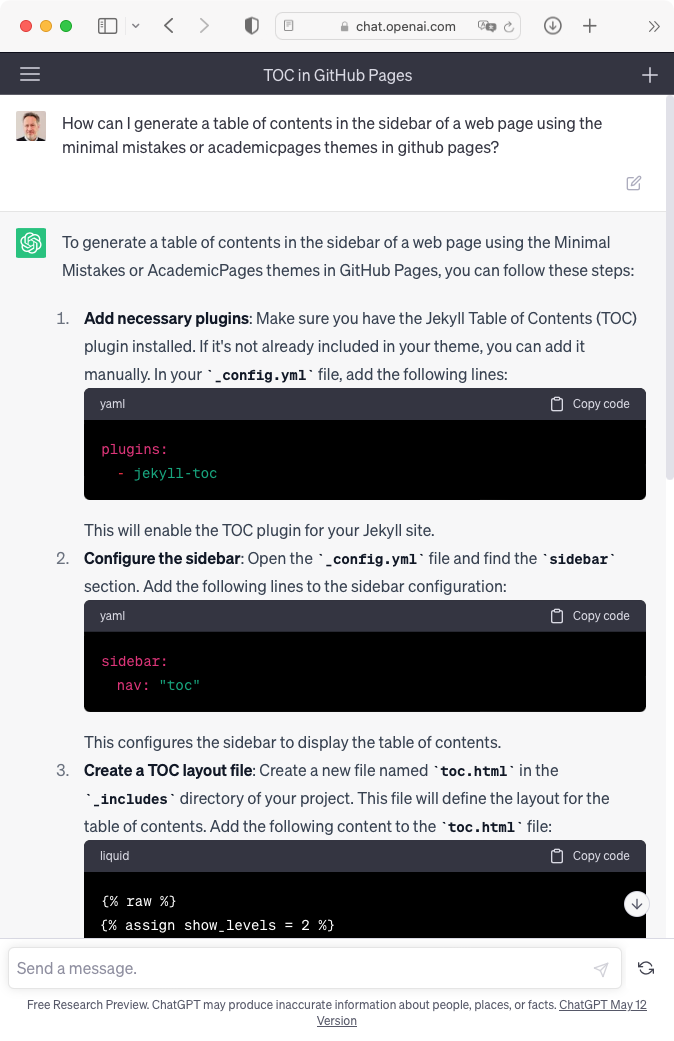

When we are at a loss, and no colleague is nearby to lend a hand, we often turn to Google and friends, which sends us to other well-known Q&A sites. The problem with the answers we find on these sites is that they lack our specific context, so we can waste considerable time on non-trivial questions to assess their relevance to our problem.

Although Stack Overflow clearly suffers from this problem, statistically-generated answers such as those provided by ChatGPT are no better, and in some ways worse, because of the high level of confidence (or hubris?) displayed by the answers.

|  |

|---|---|

| A typical Stack Overflow answer | A typical ChatGPT answer |

These screenshots show answers I obtained from Stack Overflow and ChatGPT to actual questions I had about GitHub pages. In both cases I struggled to get the information relevant for my context. Worse, the answer from ChatGPT looked authoritative, but in fact was fanciful and inaccurate.

The fact that we nevertheless tend to search for answers outside the system shows that there is a crisis that is not being addressed.

Plugins are hard to find, hard to build, and hard to compose

Instead of leaving the IDE to find answers to questions we have about our software base, it would be so much nicer if we could extend the IDE with the tools we need. Luckily there exist plugins.

Unluckily plugins are (in my experience) not pleasant to implement, it is hard to find any that are truly helpful, and they pretty much never play nicely with other plugins. Finally, plugins don’t know anything about your context, so like Stack Overflow and ChatGPT, the likelihood that they will help you for your problem is slim.

The key issue is that software is so contextual that it is not possible to predict the specific questions that will arise in developing and evolving it. (We’ll see some examples shortly.) As a consequence, generic tools and plugins will always fail to be useful at some point. Instead, we need to be able to cheaply and quickly build or adapt tools to answer our specific, contextual questions.

Moldable development

The IDE is more than a text editor. For a software system to be explainable, it must be explorable.

- First, instead of starting to explore a system from source code, we can start from a live object and navigate from there.

- Second, we must be able to answer questions relevant to our context. Instead of using off-the-shelf tools or plugins, we should be able to cheaply build composable tools specific to our domain.

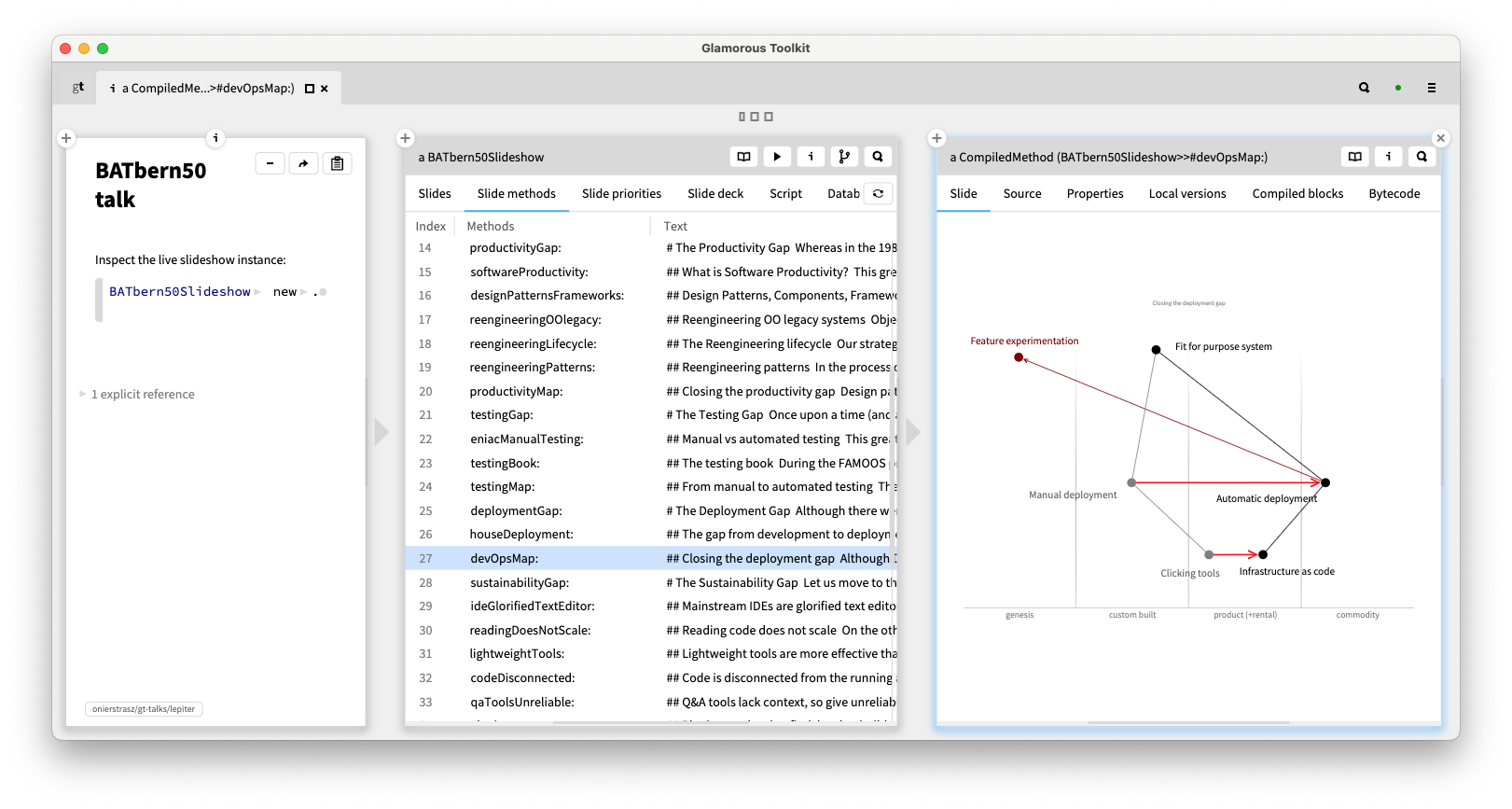

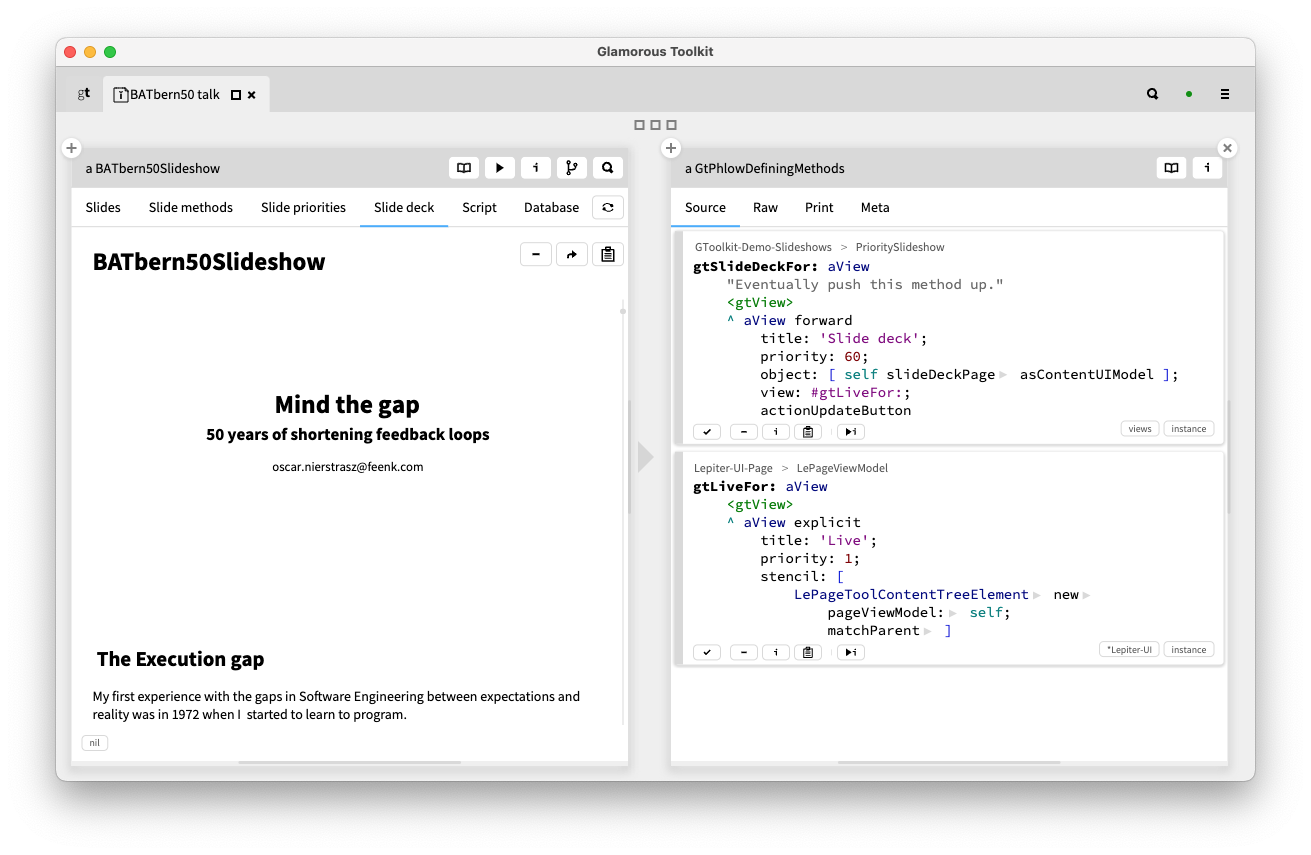

For example, to understand the slideshow implementation of the talk this blog post is based on, we don’t start from the source code but from a live instance. We can navigate from the slideshow to its slides, to the Wardley maps, or even to the source code, if we need to.

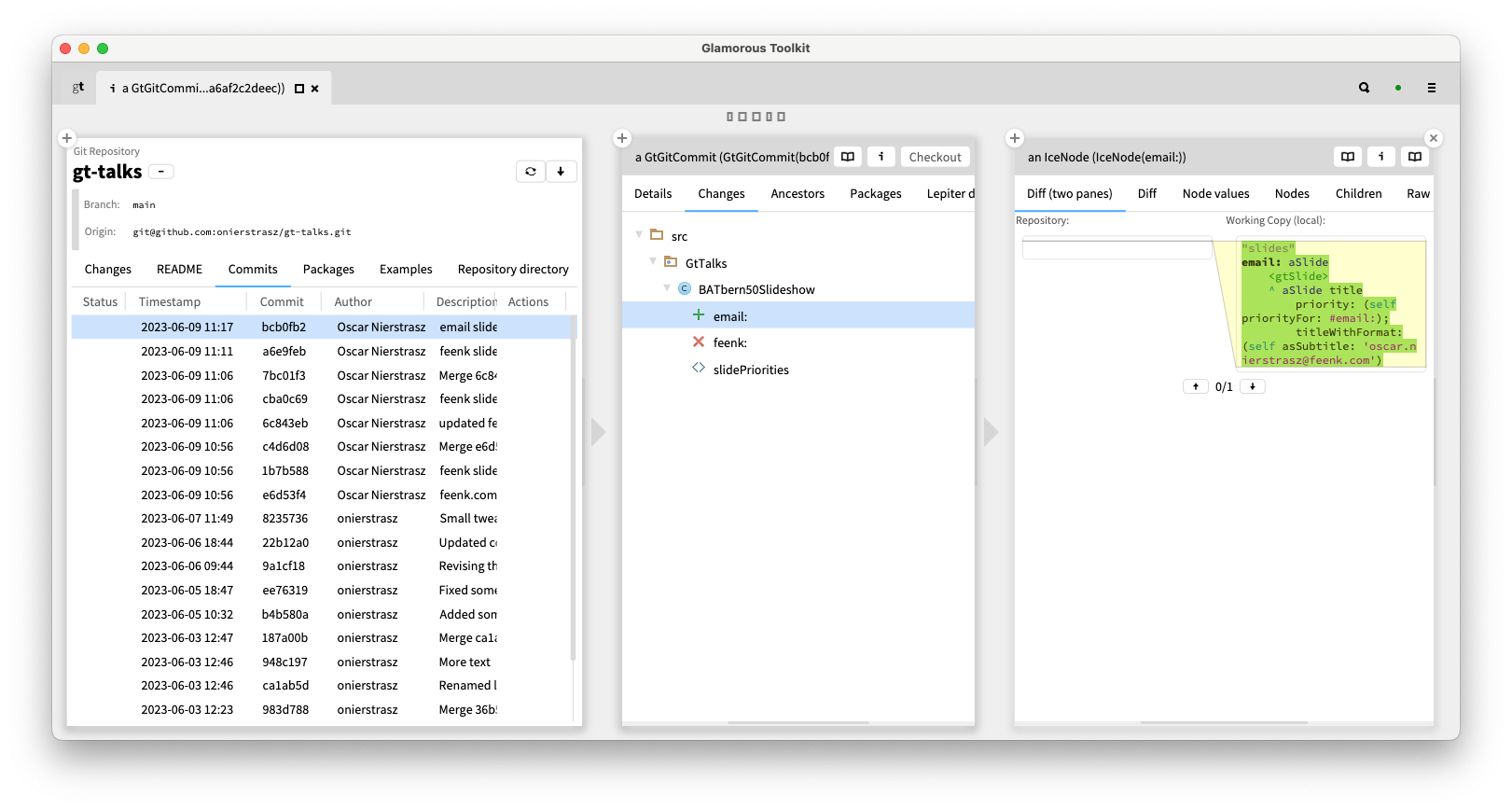

In this screenshot, we create an instance of the BATbern50Slideshow class, and inspect it in the Glamorous Toolkit (AKA GT), an open-source, moldable environment for authoring explainable systems. We can explore, for example, the Slide methods view to see the methods in order, and for each method we see the Slide view, the source code, or other views.

We can similarly explore any kind of system to understand it. Here we explore the git repository of the slideshow’s source code. We can explore the changes, the commits, the packages, and from each entity navigate further to deepen our understanding.

It doesn’t matter whether the domain is that of slideshows, git repositories, computer games, social media data, or life insurance policies. In any of these cases, we can navigate through the network of domain objects to answer our questions, or to navigate from the objects to the code, rather than the other way around.

To make systems explainable, you need to be able to add cheap, composable tools, such as views. Understanding doesn’t arise simply from navigating, but from being able to navigate efficiently and effectively to the answers you need. This implies that you need to be able to easily and cheaply define your own plugins to mold the IDE to your needs.

For each of the custom navigational views we have seen, a few lines of code are all that are needed to define them. We can ALT-click on the tabs to see the code. For example, the Slide deck view is extremely short, and leverages the fact that all the parts are composable.

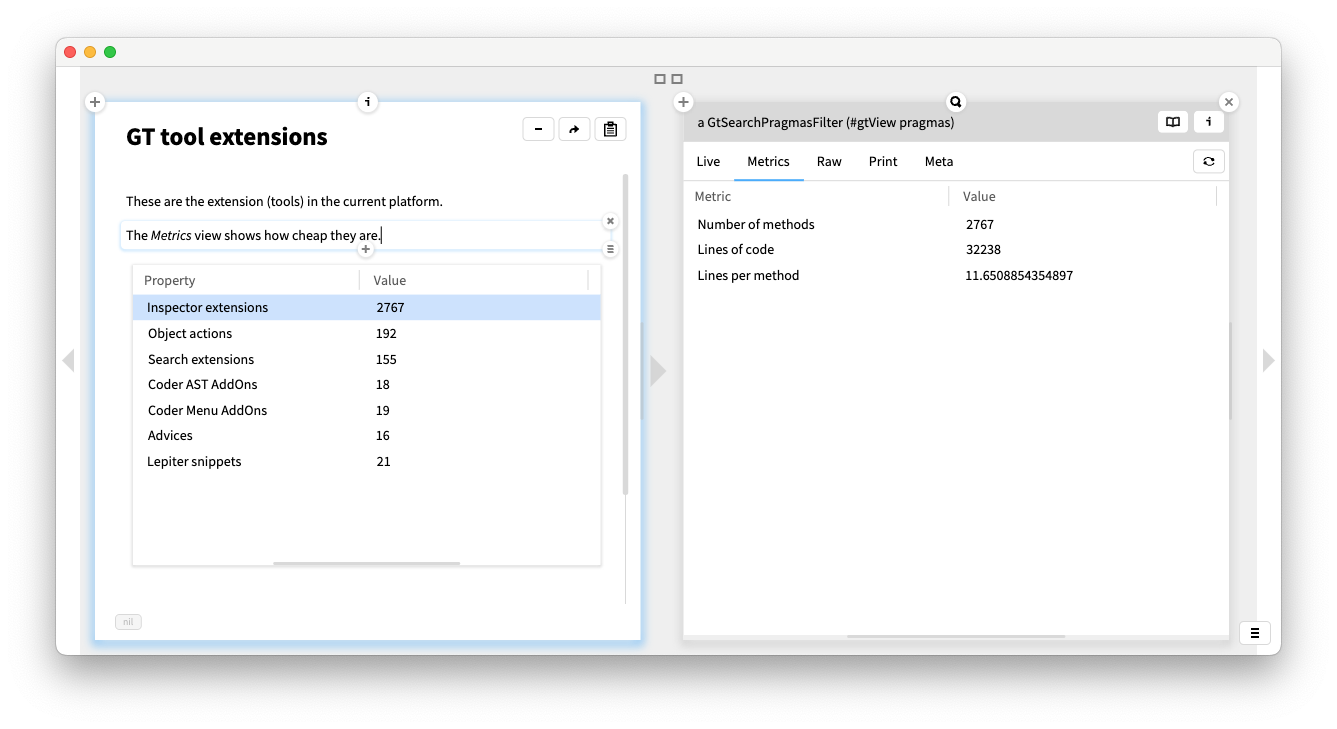

All the views we have seen are examples of custom tools added to a moldable IDE. In addition to custom views, there are several other ways the IDE can be molded, such as by adding custom actions, search capabilities, and quality advices.

The Metrics view of each extension shows that they are generally small and cheap to implement. For example, there are nearly 3000 inspector views in the standard GT image, and they average under 12 LOC.

Example: exploring Lifeware test runs

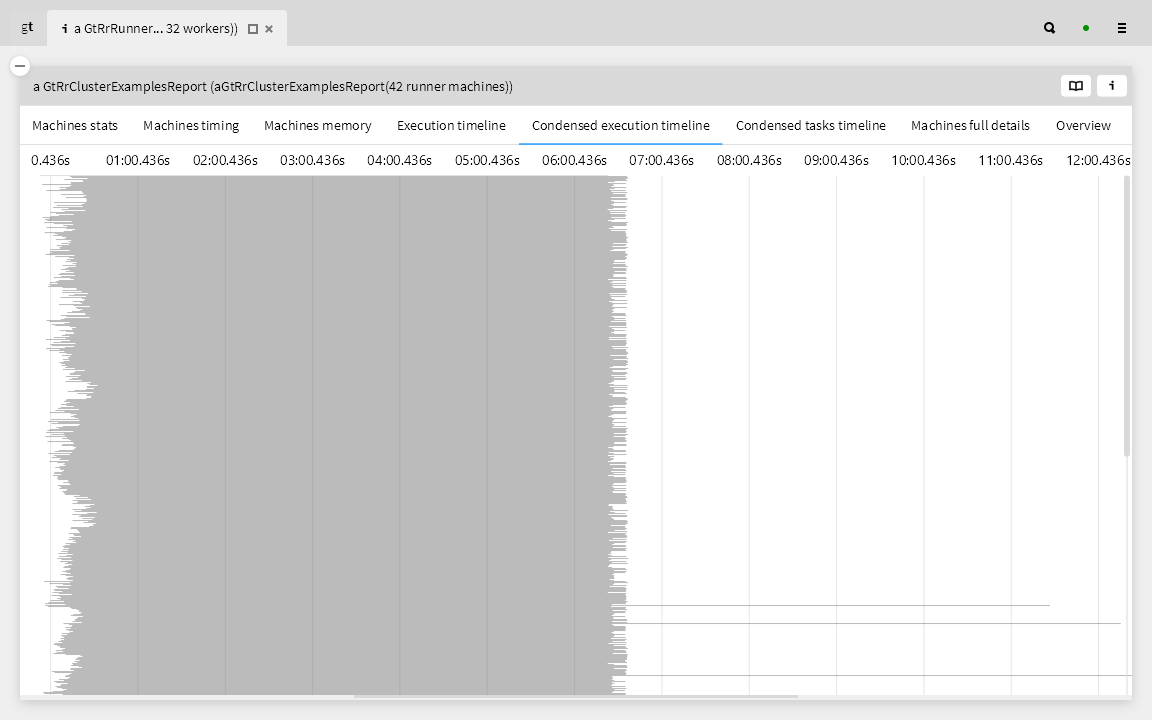

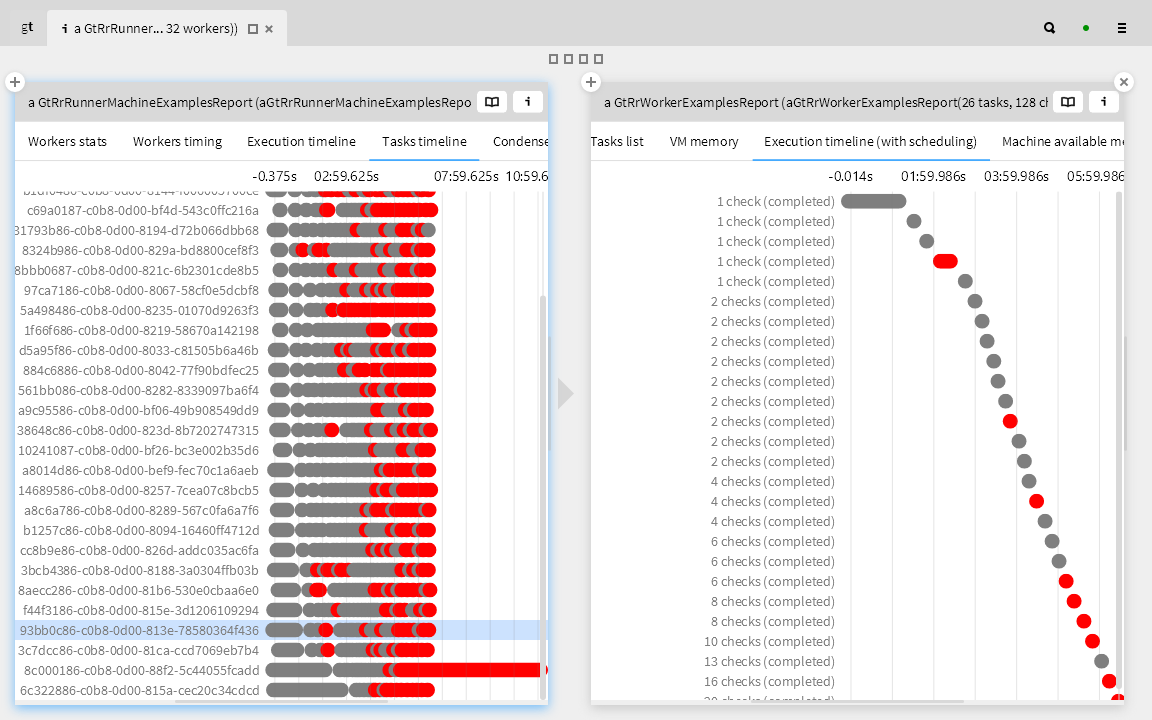

Lifeware is a company that provides software infrastructure and services for life insurance companies. Lifeware has a very large number of test cases for their life insurance SPL. These tests are run on up to 960 processors, or “workers”, on a cluster of AWS machines, each with between 16-64 processors. Each worker runs a number of test tasks. The goal is to run all the tests within 8 minutes, but because tests can take varying lengths of time to complete, this goal is not so trivial to reach.

The moldable development strategy is to ask questions of the live system, and where the answers are not immediately evident, to introduce custom views to answer those questions. By creating a few custom views, we can get some insight into what’s going on in the live system.

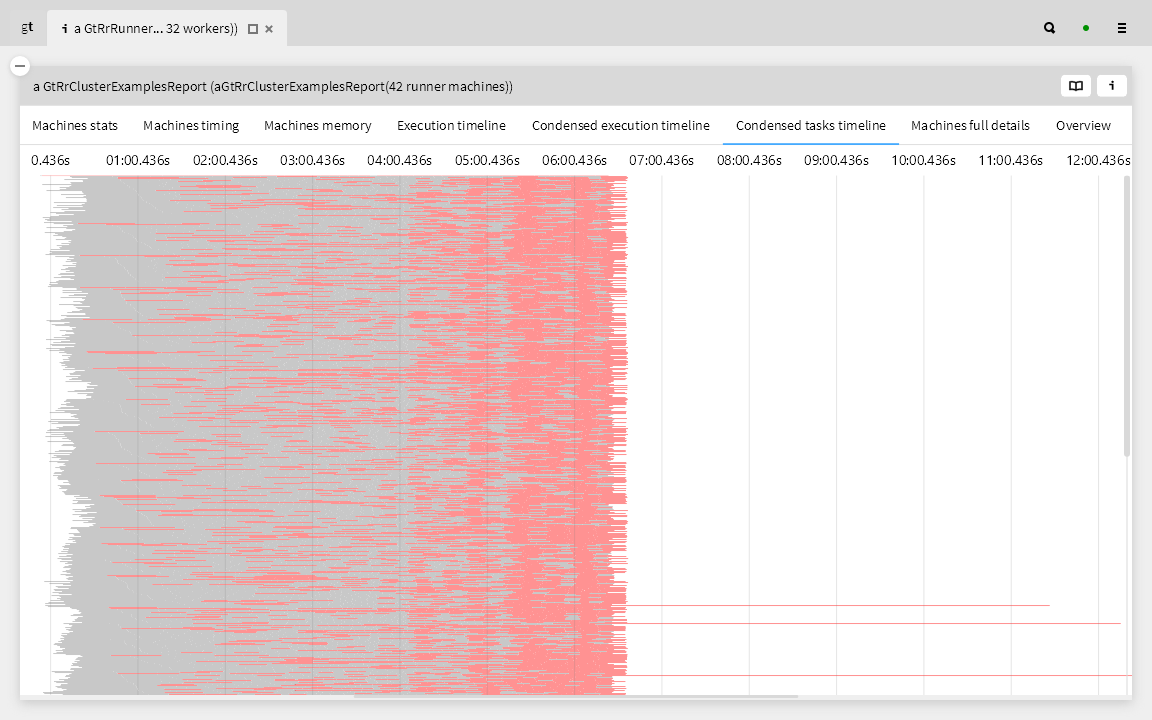

In this lightweight visualization we see that a number of workers, i.e., the long grey bars near the bottom, are taking twice as long, but why?

Here we highlight in red those tasks that took longer for the same worker than an earlier task. This tells us that there are scheduling issues, and not just with the slowest workers.

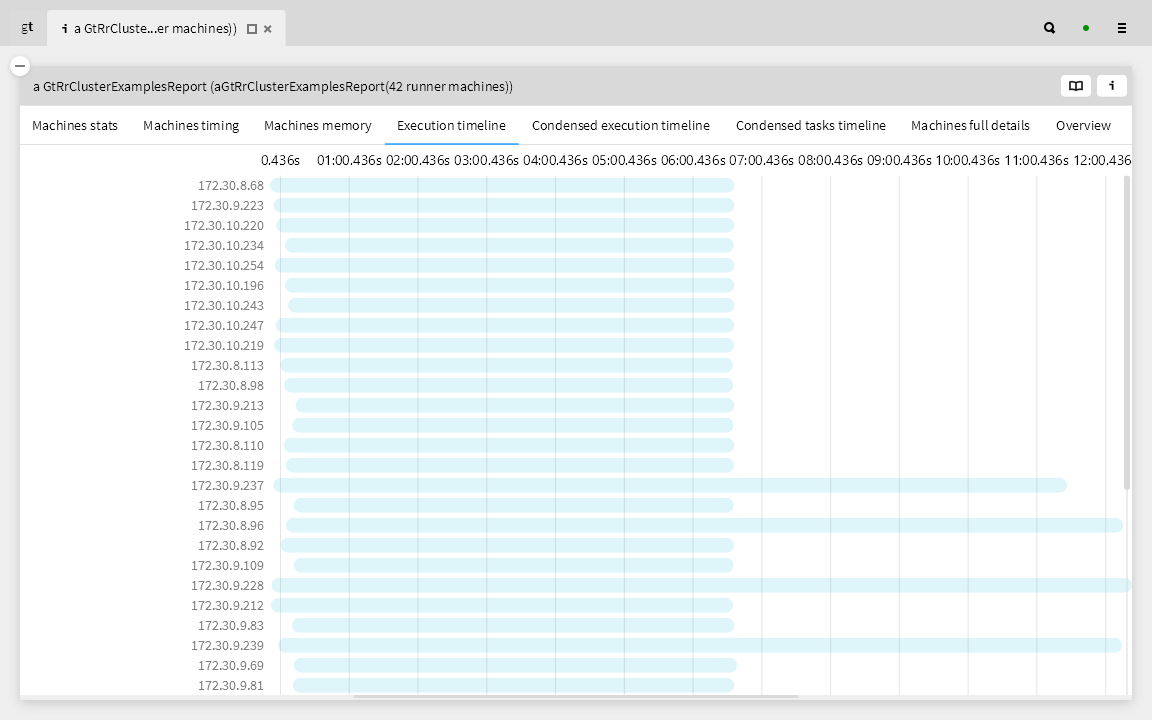

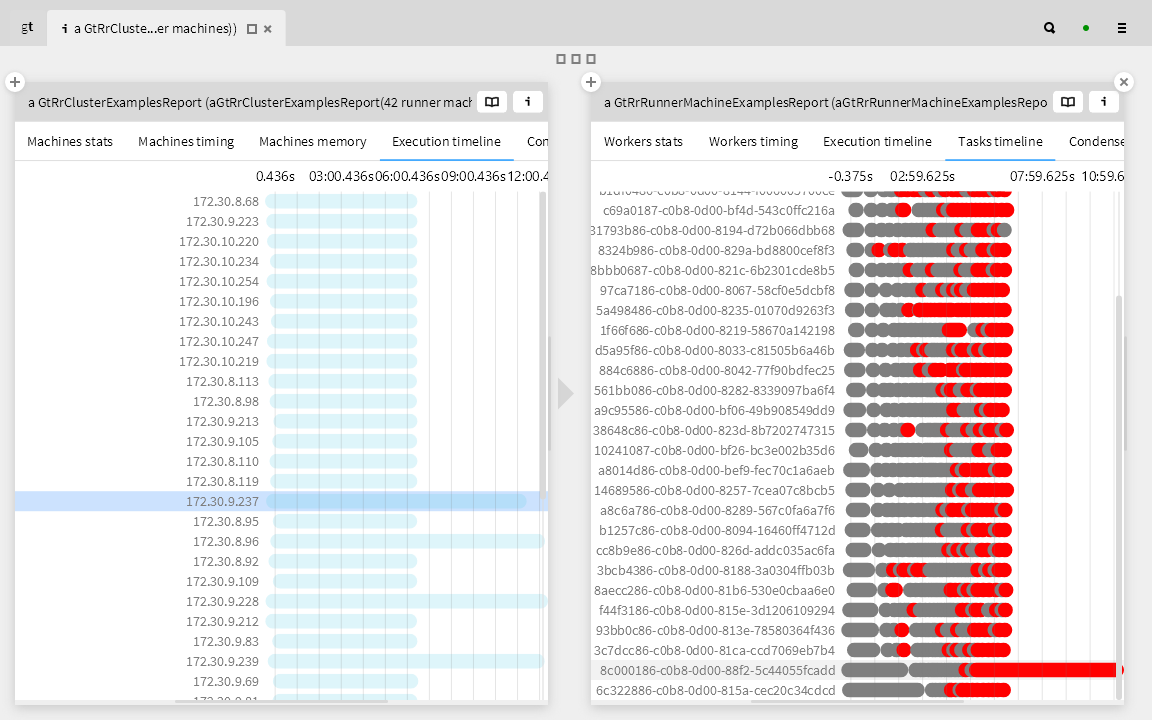

Since the machines in our cluster are not all the same, we ask if the scheduling issues are related to particular machines. Here we inspect the execution timelines of all the workers on a given machine. We see that just a few machines are having problems meeting the deadline. Is there something special about these machines?

We dive into a particular machine to see what’s going on. We can see clearly that only one worker (second from the bottom at the right) is having scheduling issues, so it’s clearly not an issue of the specific machine.

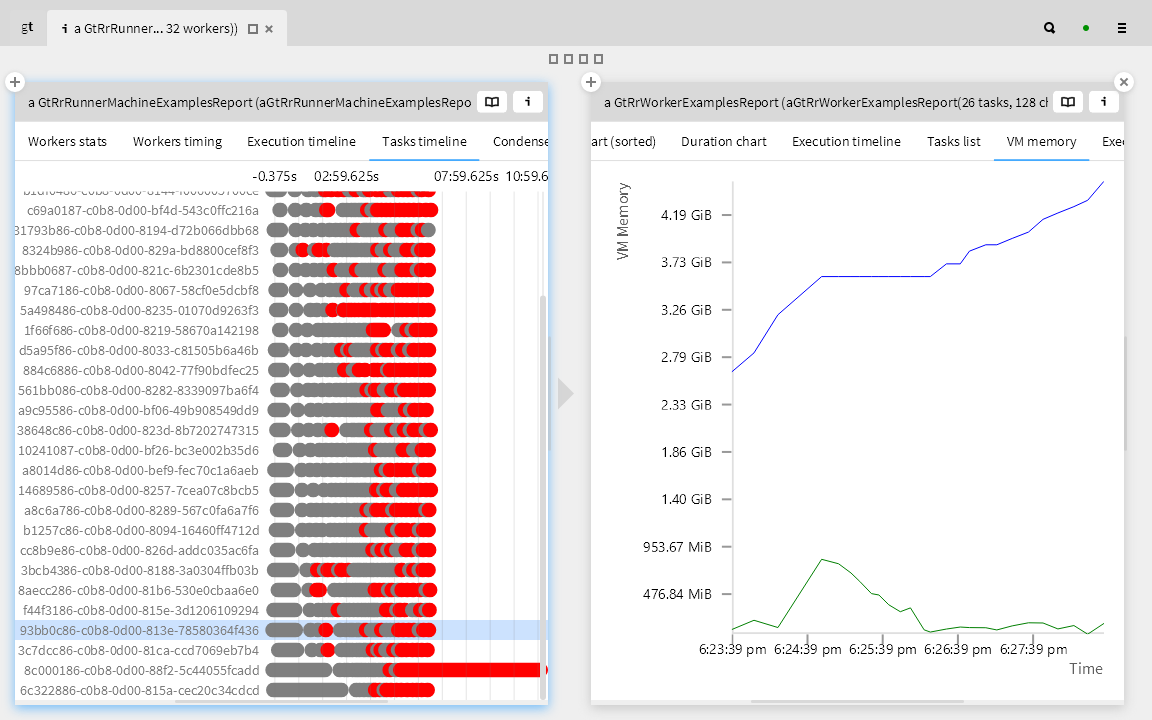

Are there issues with the memory usage? We inspect the total VM memory consumption and free memory per worker. We see nothing too unusual.

Finally we can dive into the individual tasks. Here we can verify that indeed the problem is just with the scheduling. By updating the historical data of the time taken to run each test, we can better schedule the test runs and reduce the delays.

We were able to perform this analysis because we could turn every question into a cheap and lightweight tool that would let us transform the execution data into an explorable model of the test runs.

Mapping moldable development

At the bottom here we see a transition from fixed and rigid IDE tools to moldable tools that can be easily and cheaply extended with new behavior. I have only shown you some custom inspector views, but the idea applies just as well for search tools, quality advices, and even customizable debuggers.

At the next level we see how moldable tools are leveraged by moving from manual inspection to custom queries that we plug into the tools. We saw this when we browsed the slides of a slideshow or the recent changes of a git repo. Now, instead of manually cobbling together a view, we can easily obtain a view using the molded tools.

We can have “inside-out conversations” that emerge from exploring the system itself, instead of classical “outside-in” conversations that treat the software as a black box with inputs and outputs. This then allows us to spot risks and opportunities that are observable only inside a system, and to support quick decision making not only for developers, but also business stakeholders.

Conclusion

What lessons can we draw from all this?

Programming is Modeling

First, I would say, that “programming is modeling”.

This is not a new observation, but it can be interpreted in several different ways. I found the live programming approach of APL far more exhilarating than the plodding punchcard model of programming supported by FORTRAN, but both languages suffered from a very limited view of what a program is. It was just as hard to build a clean conceptual model in APL as it was in FORTRAN.

Object-oriented programming changed that by allowing not only the design but the domain model to be reflected in the code.

I am reminded of Bertrand Meyer’s observation that he could never understand the fascination with modeling notations and CASE tools when everything is there in the code. Then one day it hit him: “Bubbles and arrows don’t crash!”

In contrast to model-driven approaches, instead of generating code from models, perhaps we are better off generating views from the code.

Programming is Understanding

We can go further, however. Kristen Nygaard, one of the inventors of Simula, the first OO language, was apparently fond of saying “To program is to understand.” I would interpret that today as meaning that software is more than just source code. It can and should be seen as a living system can expresses knowledge about itself.

I would like to propose a new mantra, namely: “The software wants to talk to you.”

This means that instead of letting the IDE lock up software inside the prison of a text editor, it should enable the exploration, querying and analysis of live systems. Then, instead of having to head to Google, Stack Overflow or ChatGPT to answer questions about our software, we should be able to answer the questions we have with the help of the systems themselves.

﹌﹌﹌﹌﹌

This blog post is based on an invited talk I gave at the 50th anniversary Berner Architekten Treffen on June 9, 2023.