SmalltalkIntroSlideshow

A bit of Smalltalk

Smalltalk is a fully object-oriented language and environment in which everything is an object. The system is live, which means that you are always developing a running system. Programming means making small incremental changes, by adding classes or methods to the live system.

Today we'll see how this impacts the sofware development process. As a running example, we'll take the Ludo game that the students developed in P2, and as a platform, we'll use GT, the Glamorous Toolkit, a moldable development environment built on top of Pharo Smalltalk.

NB:

This slideshow is available in the standard download of GT from gtoolkit.com in the class SmalltalkIntroSlideshow

.

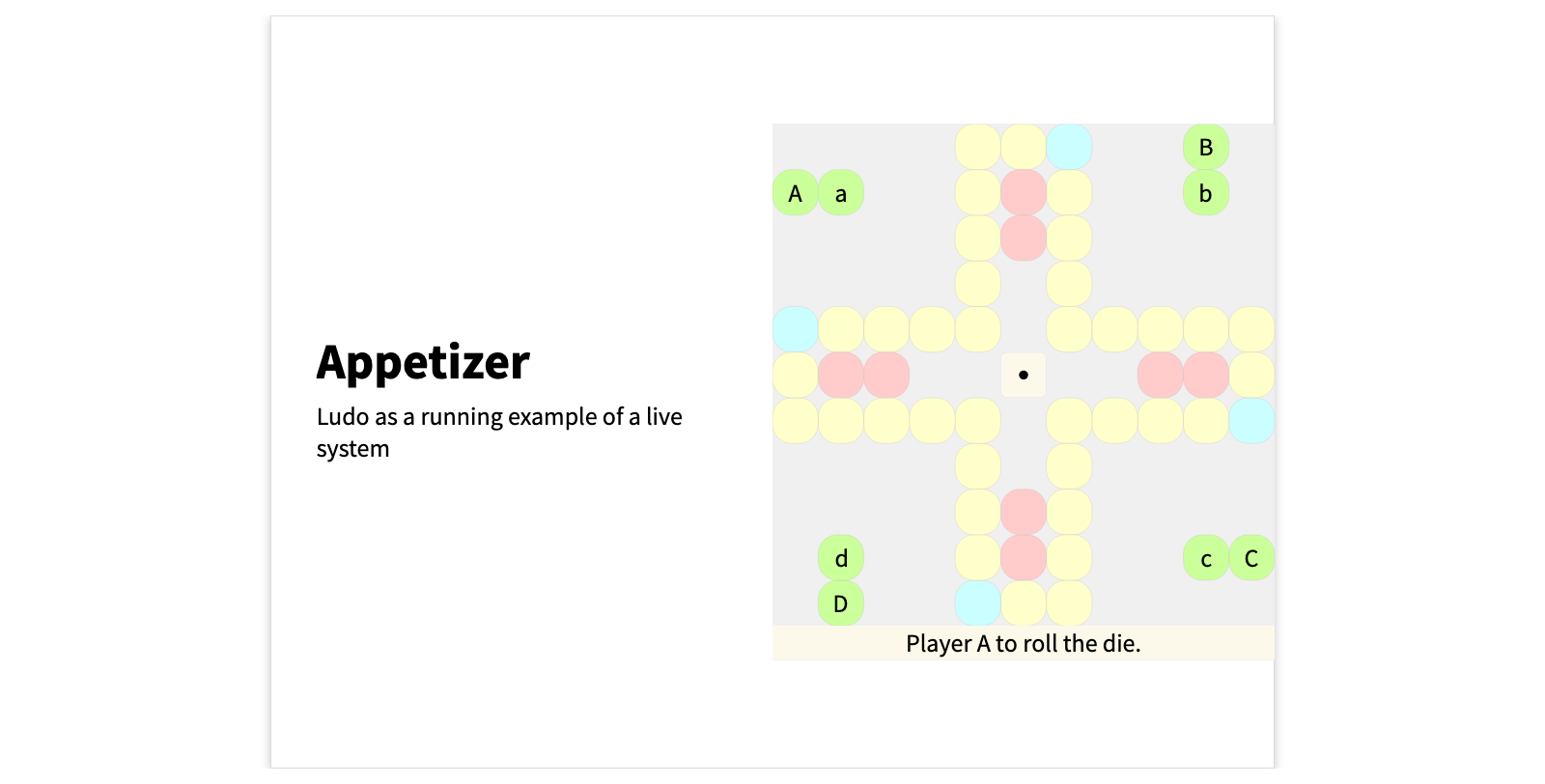

Appetizer

As an appetizer, here we see an instance of the Ludo game running in GT. We can play the game by clicking on the die and moving the pieces, but how is the game composed of objects? How can we understand how it works?

Outline

First we'll have a quick look at what Smalltalk is, and how it differs from other object-oriented programming languages and systems.

Next we'll have a quick look at the basics. Smalltalk is a tiny language, and you can learn the syntax in a few minutes, but it does take a bit of getting used to.

Then we'll proceed with the development of the Ludo game. The key idea is to make the domain concepts visible as we program, so instead of just seeing source code, we see a live system that we can explore.

Testing is similar to classical Xunit testing, with the small difference that every test returns an example object.

This turns out to be very powerful, not just for building new tests, but also for exploring the system and building live documentation.

We'll wrap up with some take home messages.

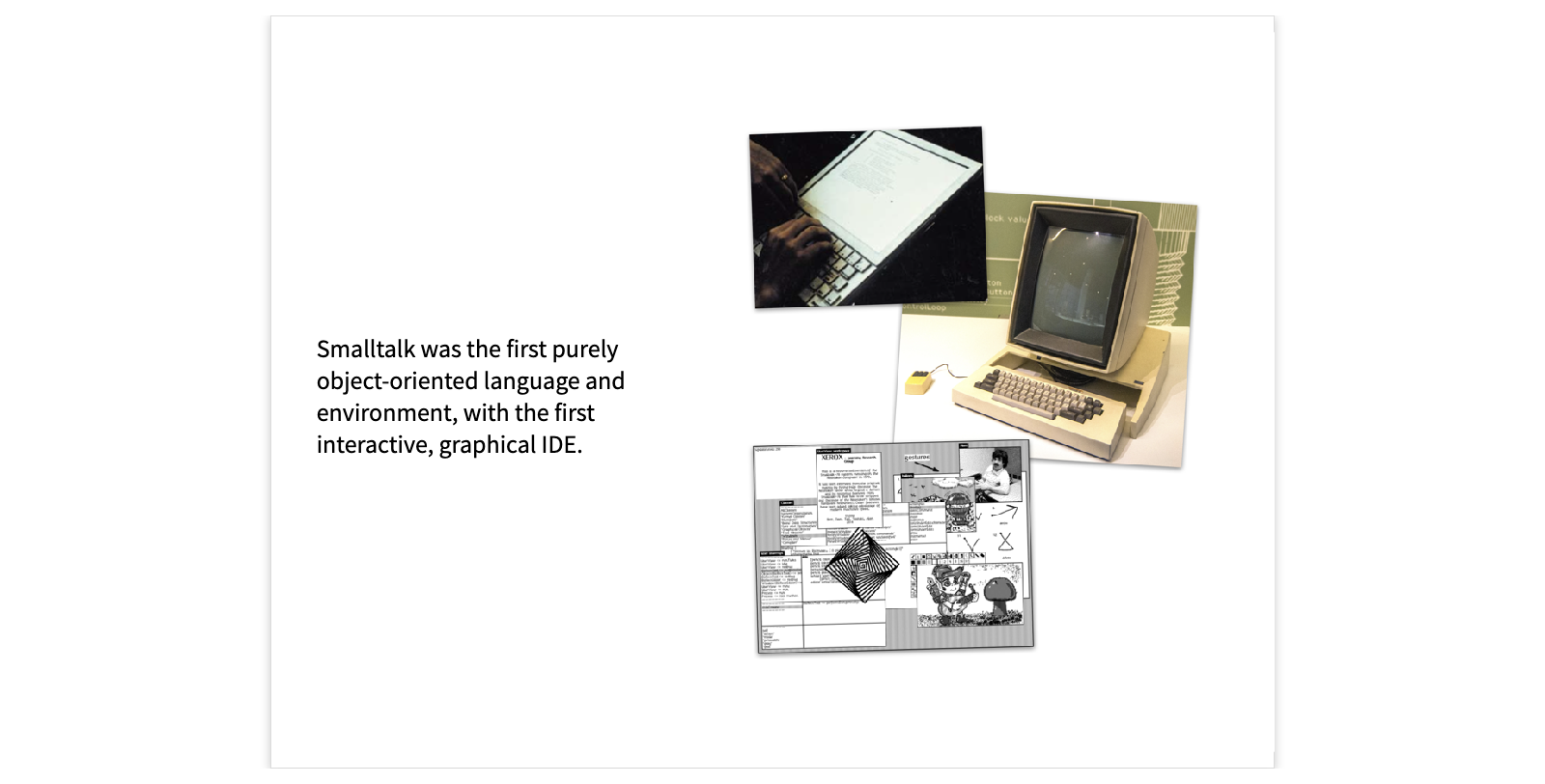

Smalltalk's origins

In the late 60s, Alan Kay predicted that in the foreseeable future handheld multimedia computers would become affordable. He called this a “Dynabook”. (The photo shows a mockup, not a real computer.)

He reasoned that such systems would need to be based on objects from the ground up, so he founded a lab at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) to develop such a fully object-oriented system, including both software and hardware. They developed the first graphical workstations with a windowing system and mouse.

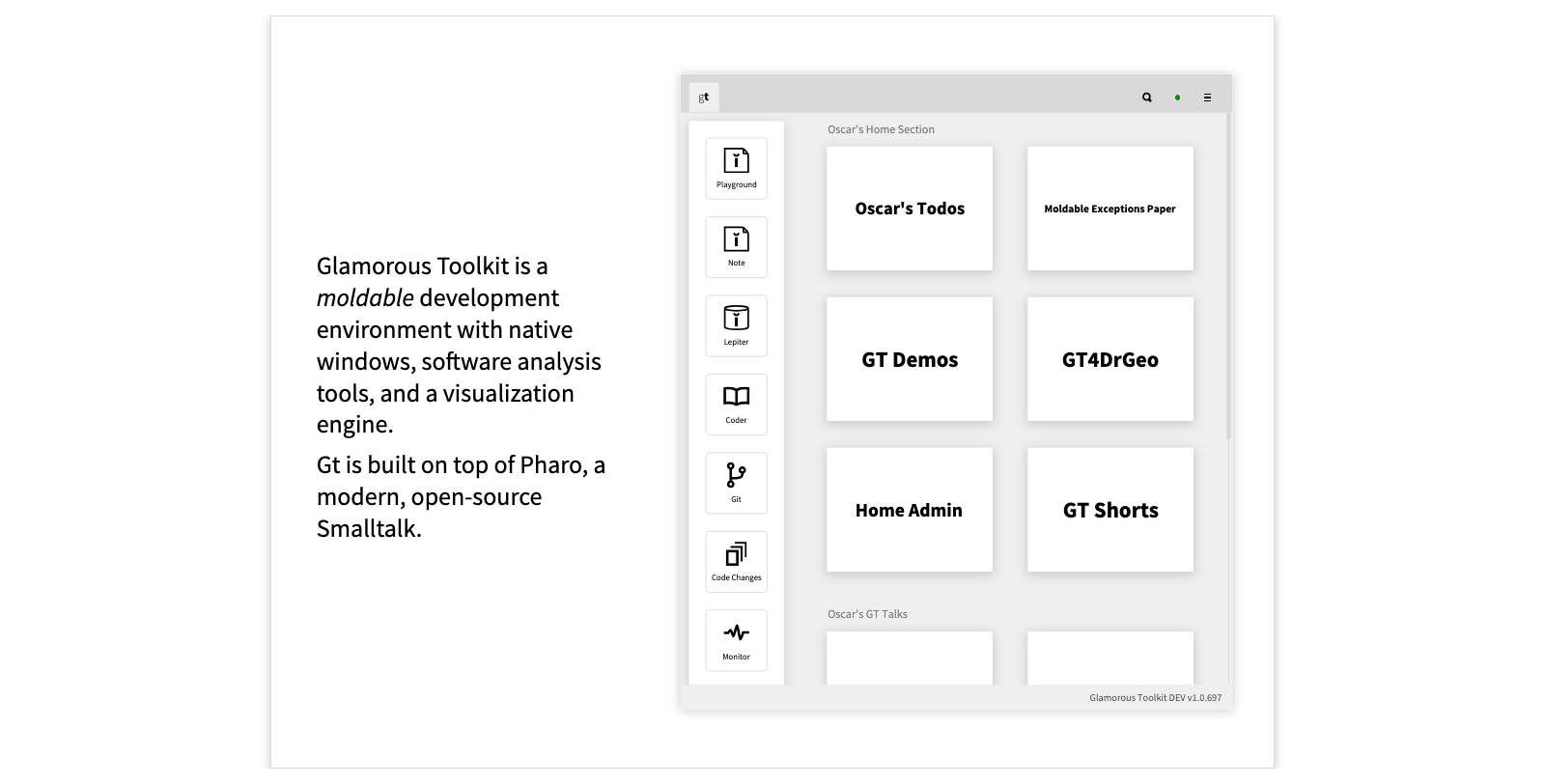

Glamorous Toolkit

GT is a moldable development environment, in which the development tools can be easily extended with application-specific behavior. We'll see examples of this with the Ludo game implementation.

GT is built on top of Pharo, a modern, open-source Smalltalk system.

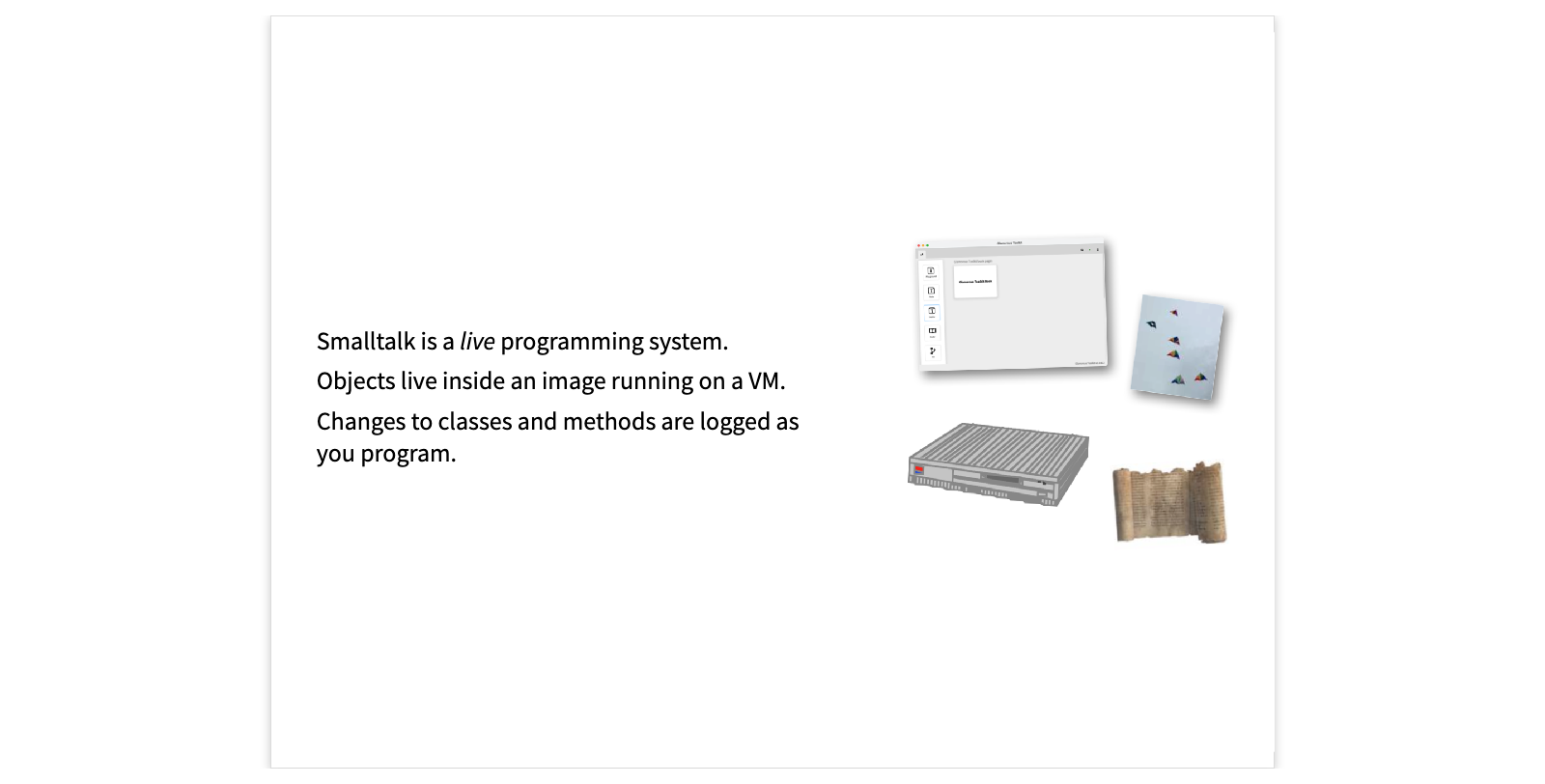

Smalltalk is a live programming system

There are four parts to a running Smalltalk system. (1) The image is a snapshot of all the live objects in the system. When you start Smalltalk, all the objects are loaded from the saved snapshot into the live image. (2) The changes file logs all changes to the source code, namely classes and methods. This means that your source changes cannot be lost, and can be replayed in case of a system crash. (3) The virtual machine executes the bytecode of compiled methods. (4) The sources store the source code of the system itself, so you can access, and potentially change anything.

Two rules

To really understand Smalltalk, there are two important rules to remember.

First, pretty much everything in the system is an object. There is no distinction between objects and primitive data types. Also everything in the environment is an object. This means that you can work with the system in a very consistent and uniform way.

Second, everything happens by sending messages to objects. If you want an object to do something, you send it a message. The object then sees whether it has a method for handling that message, possibly inherited from a superclass.

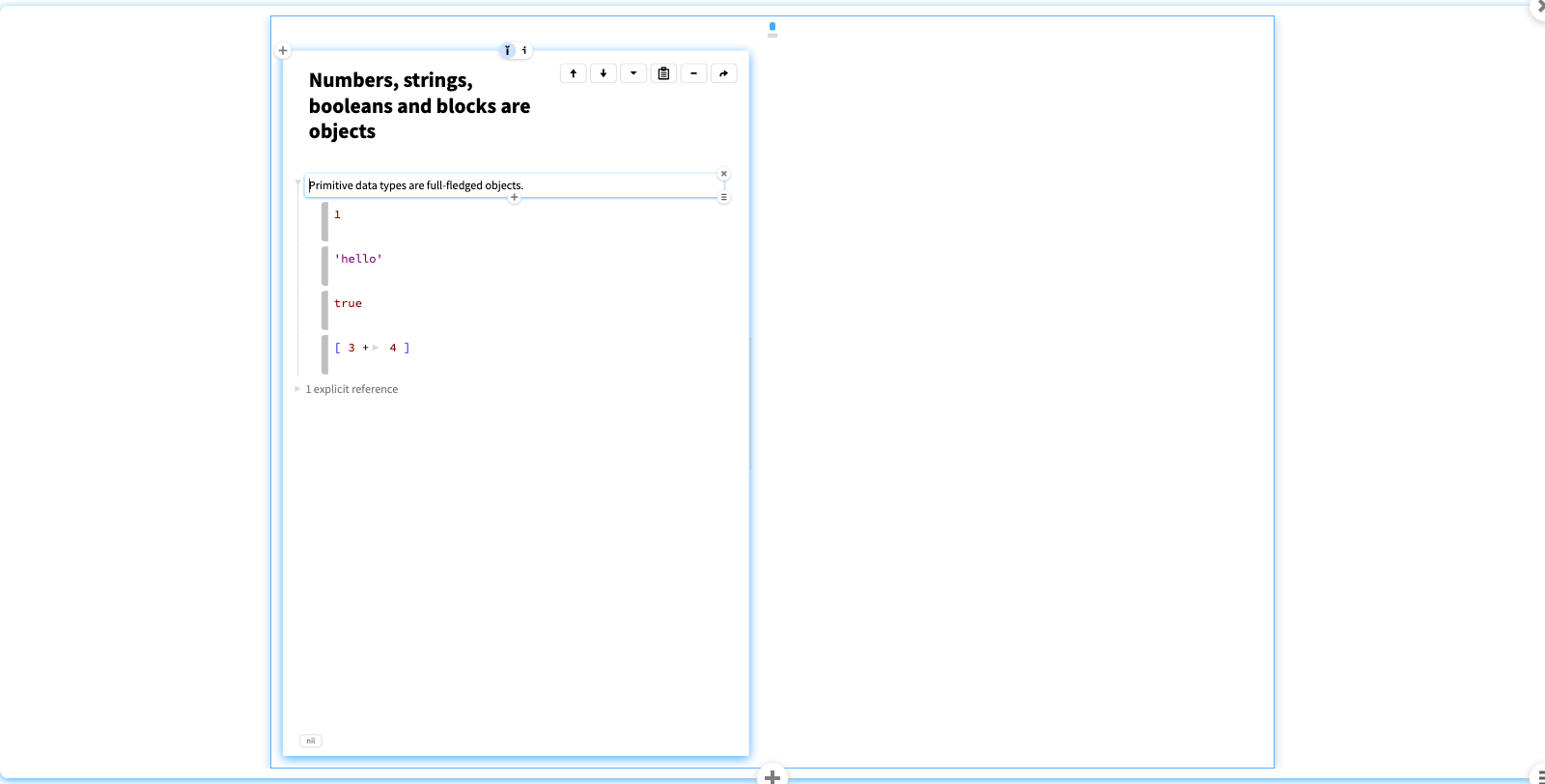

Numbers, strings, booleans and blocks are objects

Here we see a Notebook page containing both text and code snippets.

We can evaluate and inspect the results of the code snippets.

Numbers are objects, not just primitive data types. We see that the number 1 is an instance of the SmallInteger class. Strings are delimited by single quotation marks. If we inspect a string, we see it is made of of characters, such as $h. The dollar sign preceeds a printable character.

Even booleans are objects. true is an instance of the class True, which is a subclass of Boolean.

Blocks, or anonymous functions, are delimited by square brackets. This one takes no arguments, so we can evaluate it by sending it the message value.

- Inspect the snippets.

- Change the last snippet to send value to the block.

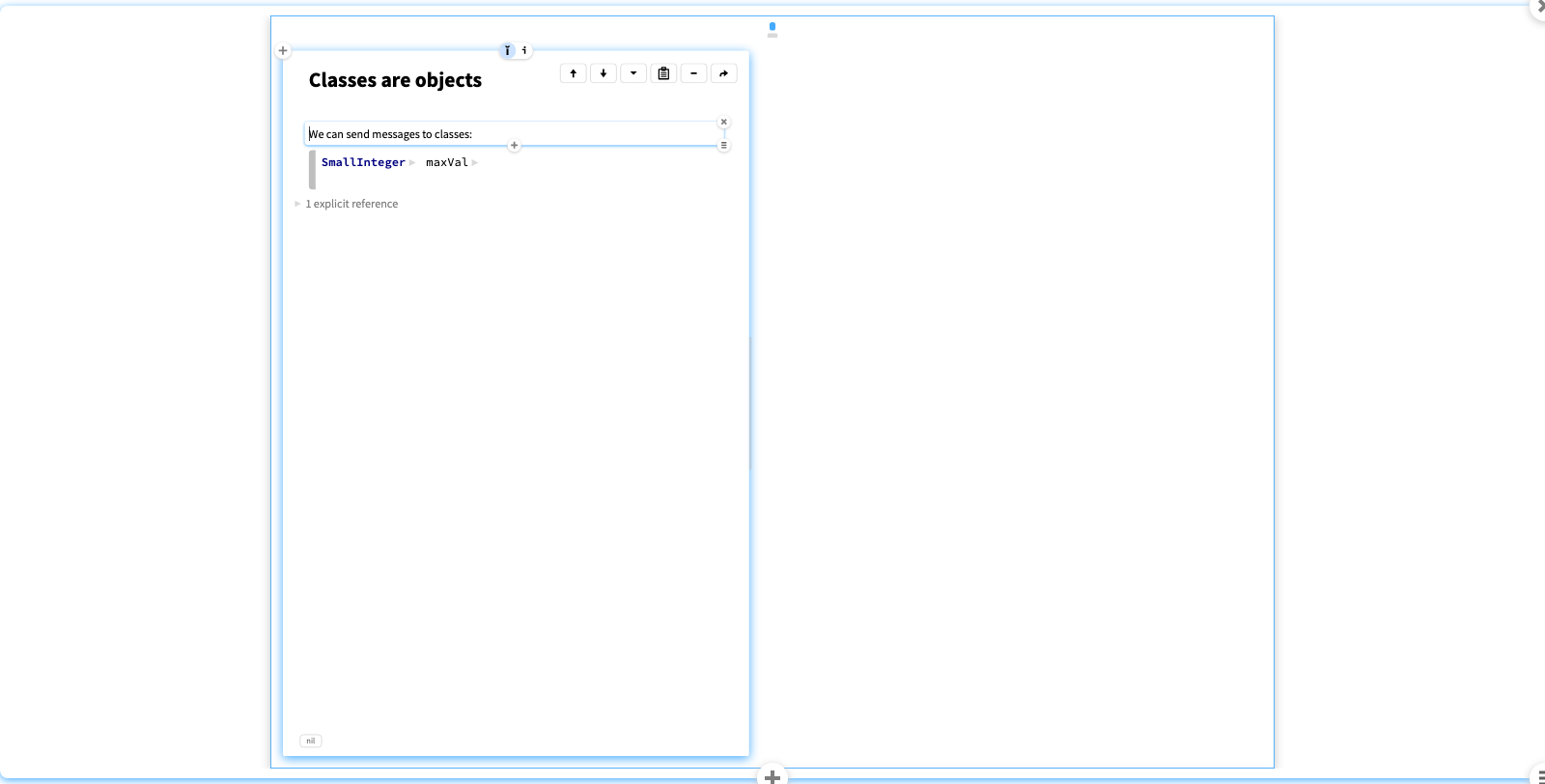

Classes are objects

Classes are objects too. A class is a global name that starts with an upper case letter, such as SmallInteger. We can browse the source code of a class by opening the code bubble, by using the context menu, or using a keyboard shortcut.

We can send messages to classes, such as SmallInteger maxVal. What do you suppose will be the result of sending + 1 to this maximum value?

- Inspect the snippet

- Send self + 1 in the integer's playground

- Note the result type

- Send self - 1 in the playground

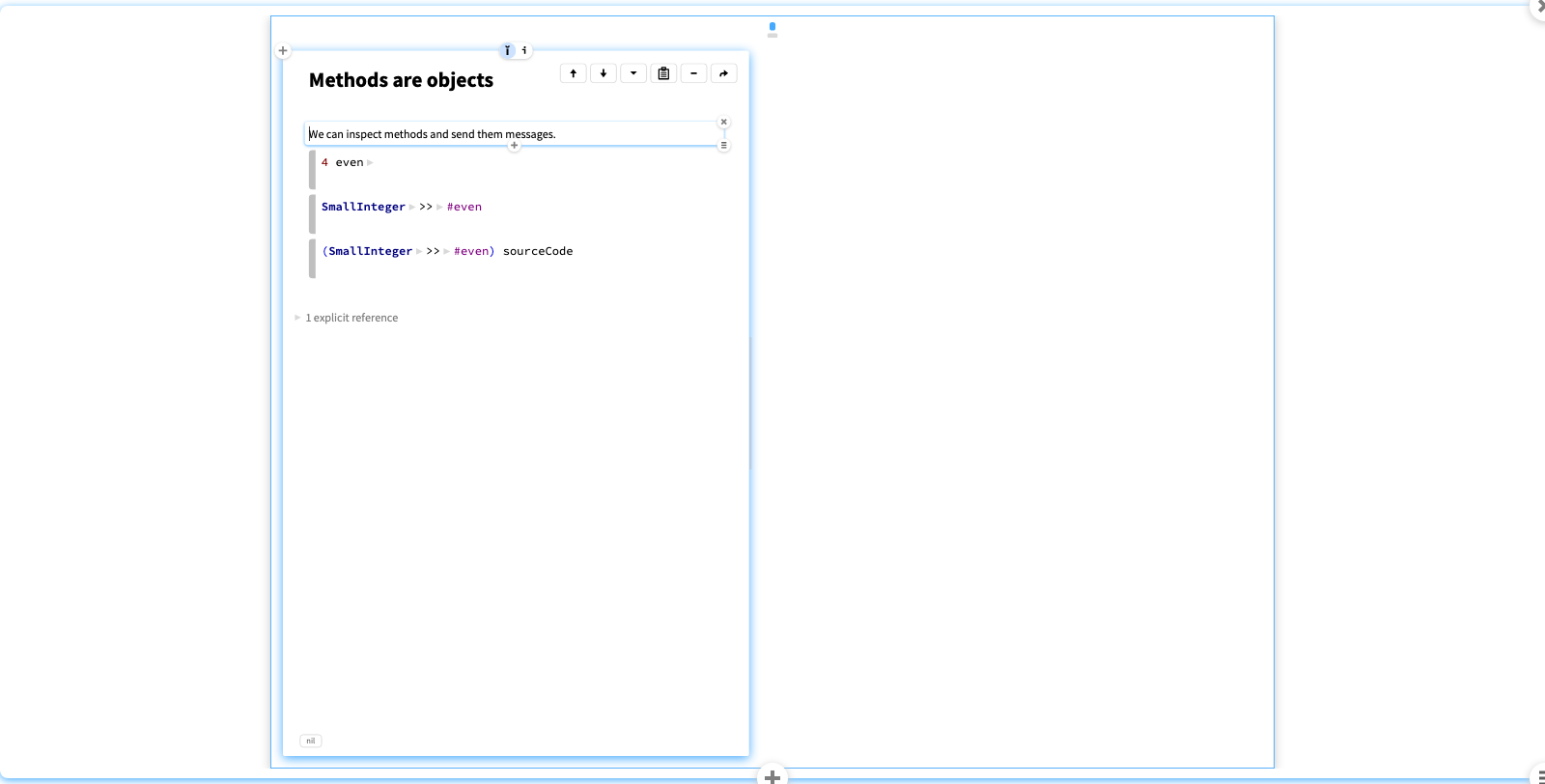

Methods are objects

A method is also an object. You can retrieve it by sending the message >> to the class with the method's selector as an argument.

If you inspect a method, you can see not just its source code, but also its bytecode and even the abstract syntax tree.

- Inspect the snippets - Explore the views of a method

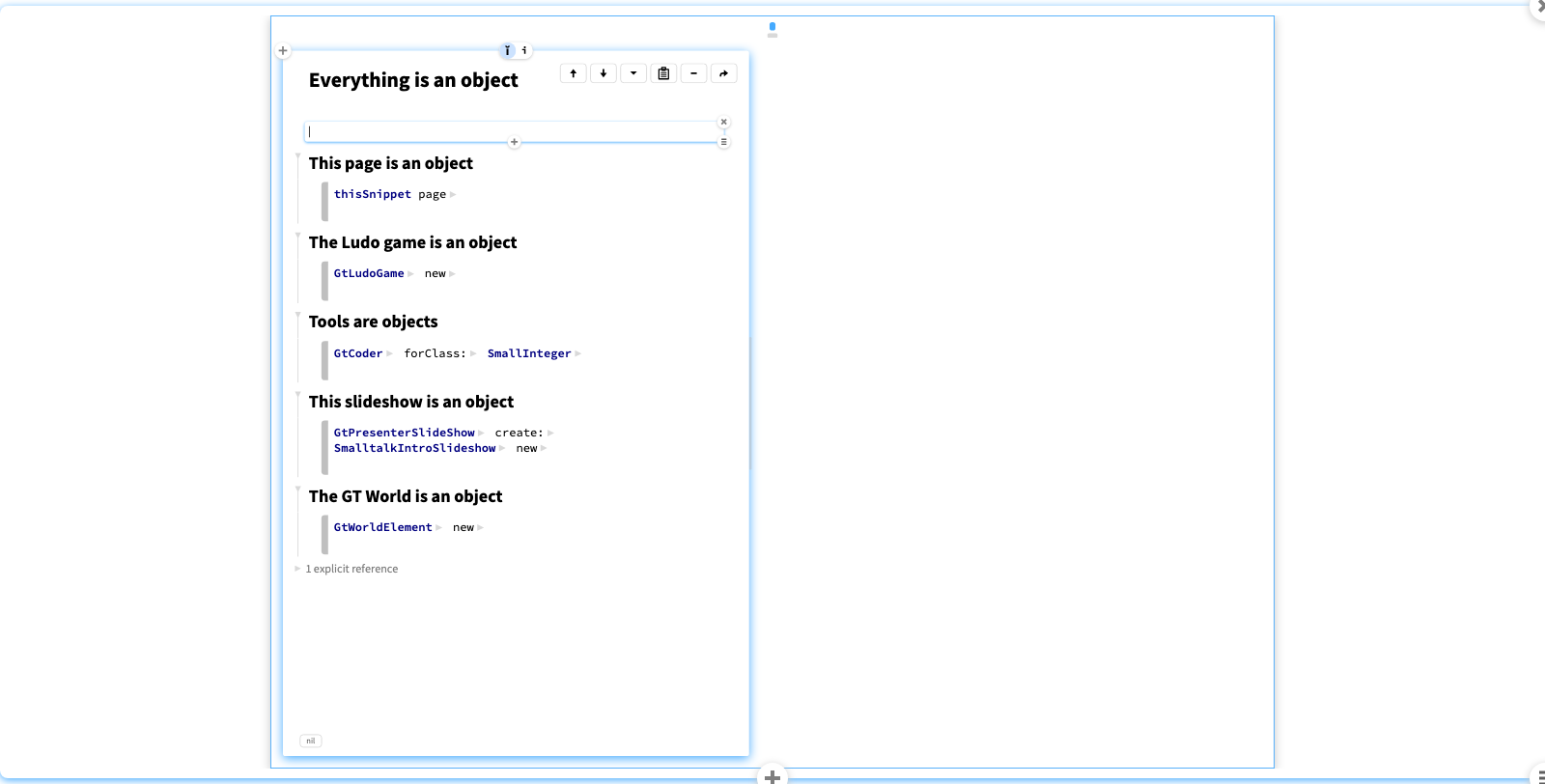

Everything is an object

A method is also an object. You can retrieve it by sending the message >> to the class with the method's selector as an argument.

If you inspect a method, you can see not just its source code, but also its bytecode and even the abstract syntax tree.

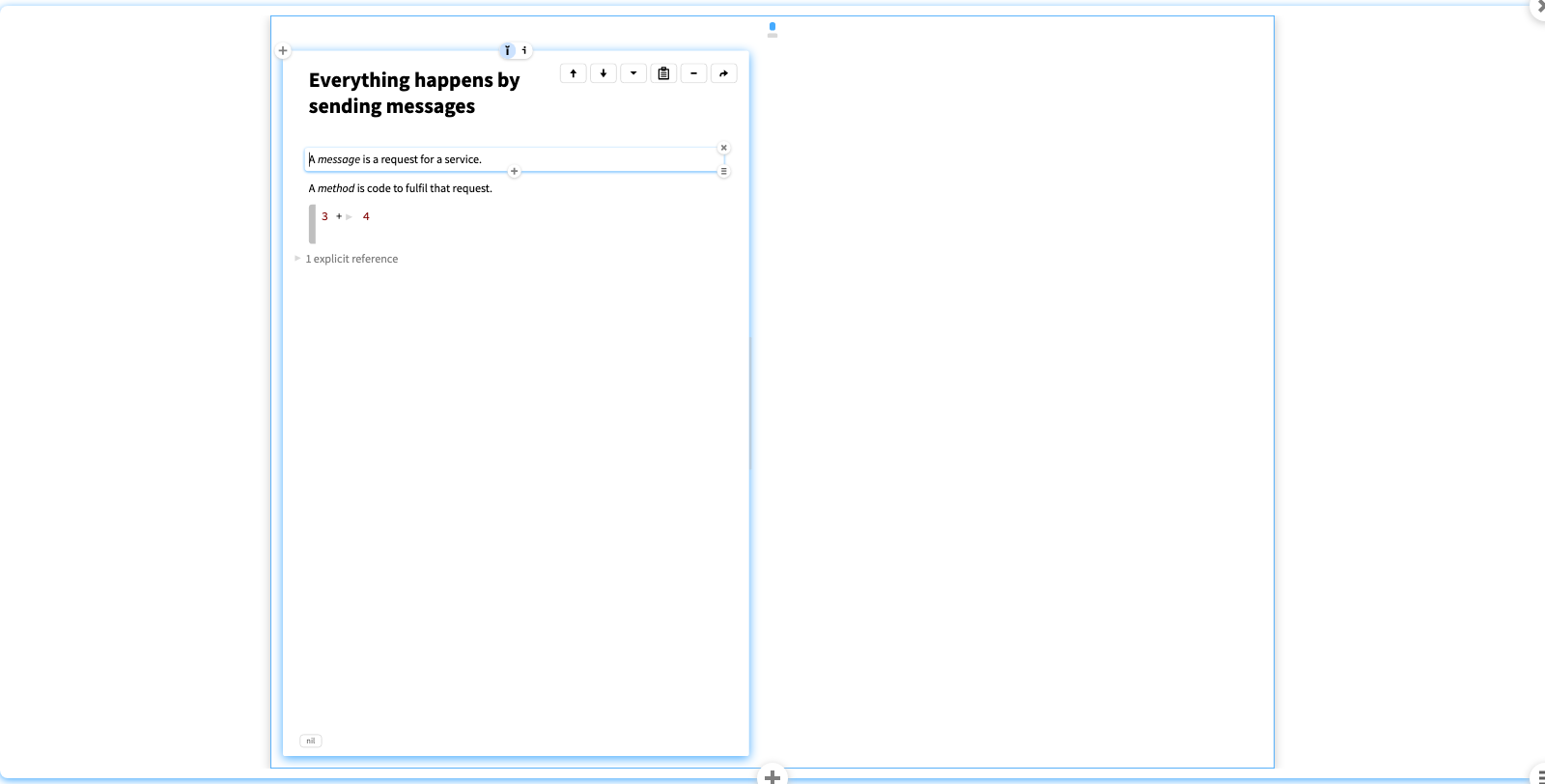

Everything happens by sending messages

Smalltalk introduced the metaphor of “methods” — you do not “invoke a method” (which makes no sense linguistically), but rather you “send a message to an object” , and it determines whether it “understands the message” and has a “method” for responding to it.

The expression 3+4 is a

message

“+4” with the

selector

“+” and argument 4 sent to the

receiver

3:

The receiver 3 has a

method

(a chunk of code) to compute the result.

- Inspect the result

- Open the code bubble for the + method

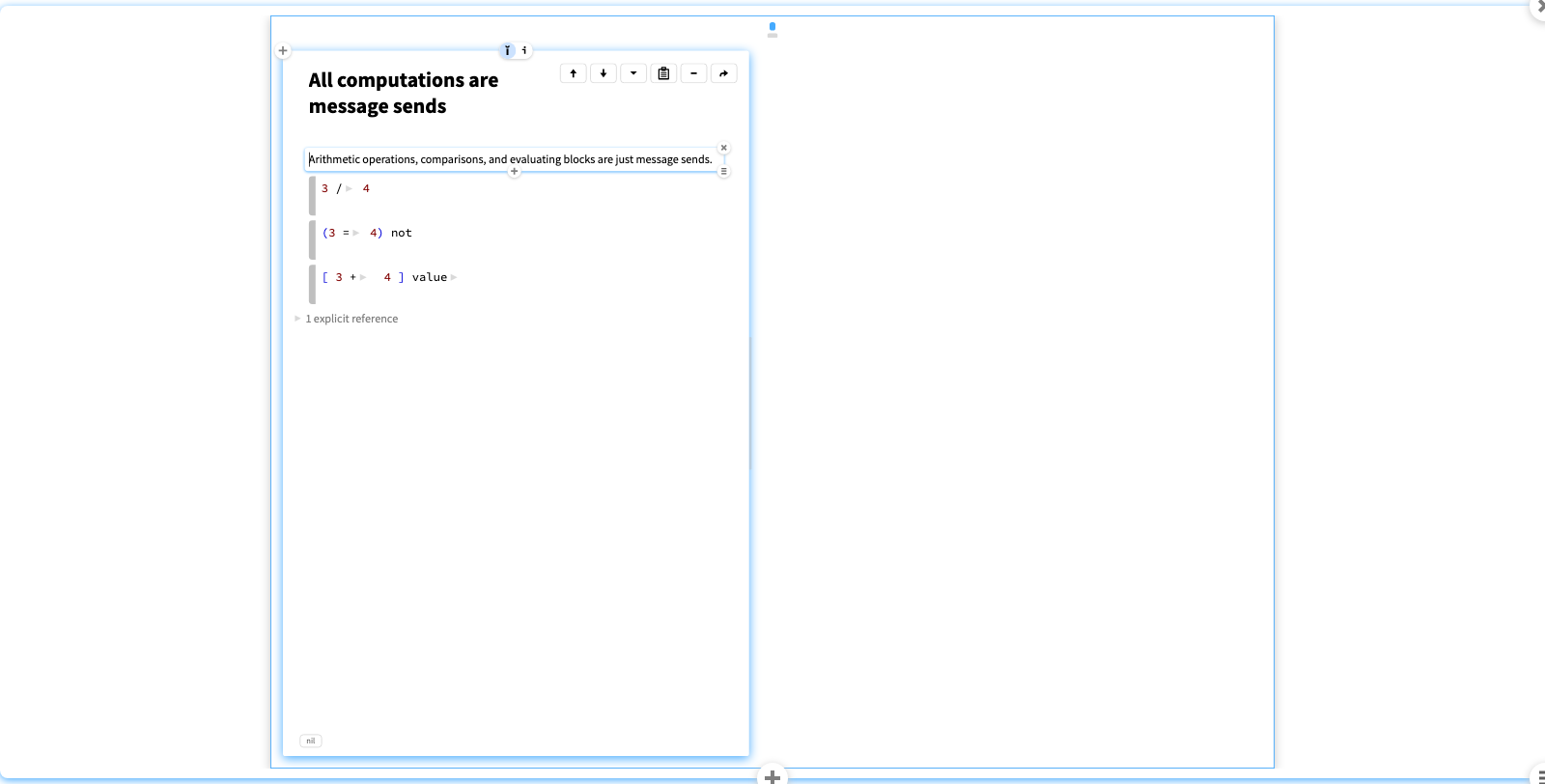

All computations are message sends

There are no built-in operators. These are all just message sends:

Sending / to a number will invoke a factory method to create an instance of Fraction

.

As in other OO languages, = tests object equality while == tests for identity. (If a class does not implement a method for =, then by default they are the same.)

You can evaluate a block by sending it a value message.

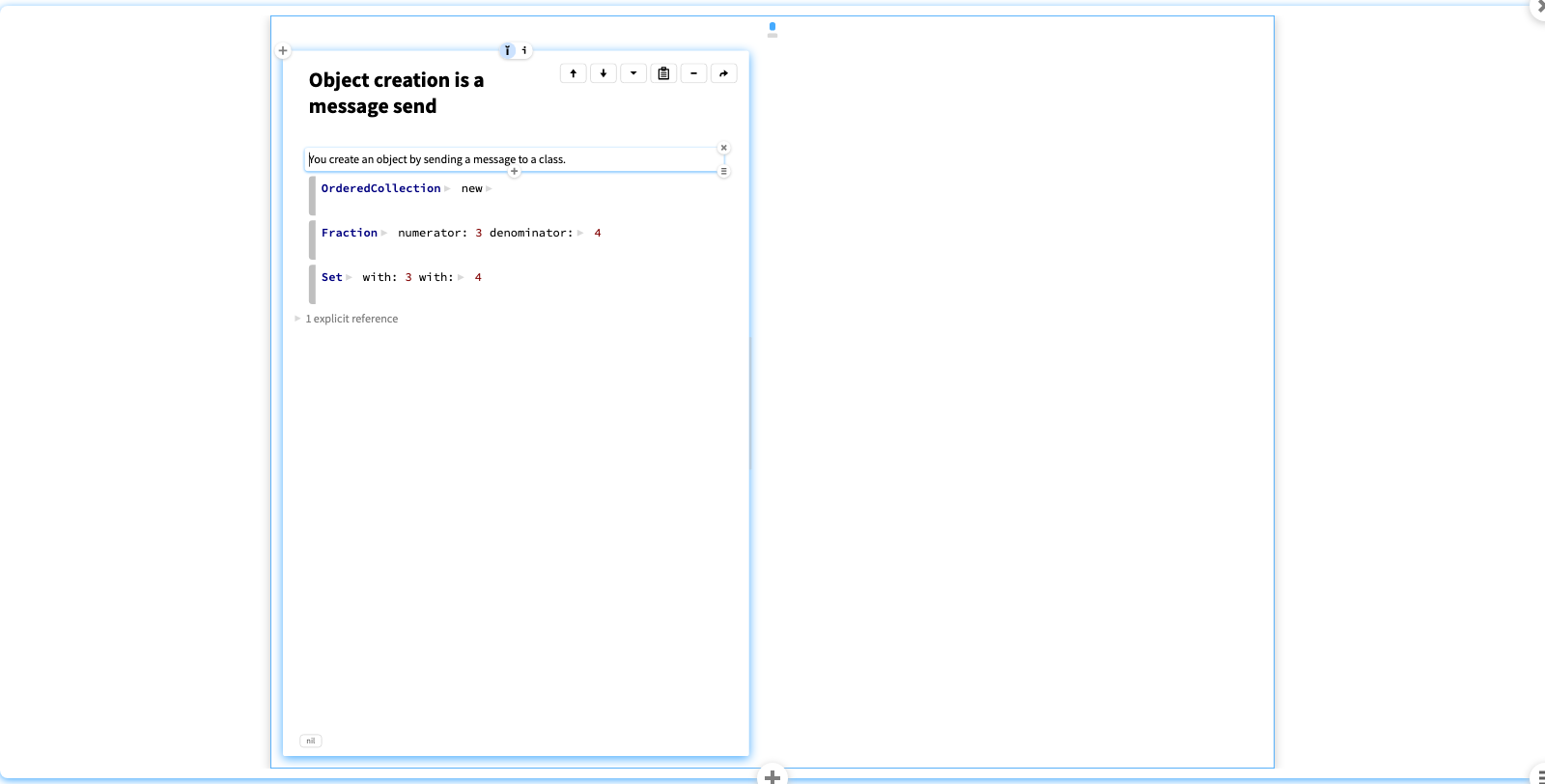

Object creation is a message send

You can send the message new to create a new instance of a class.

Many classes have constructors that take arguments to initialize instances.

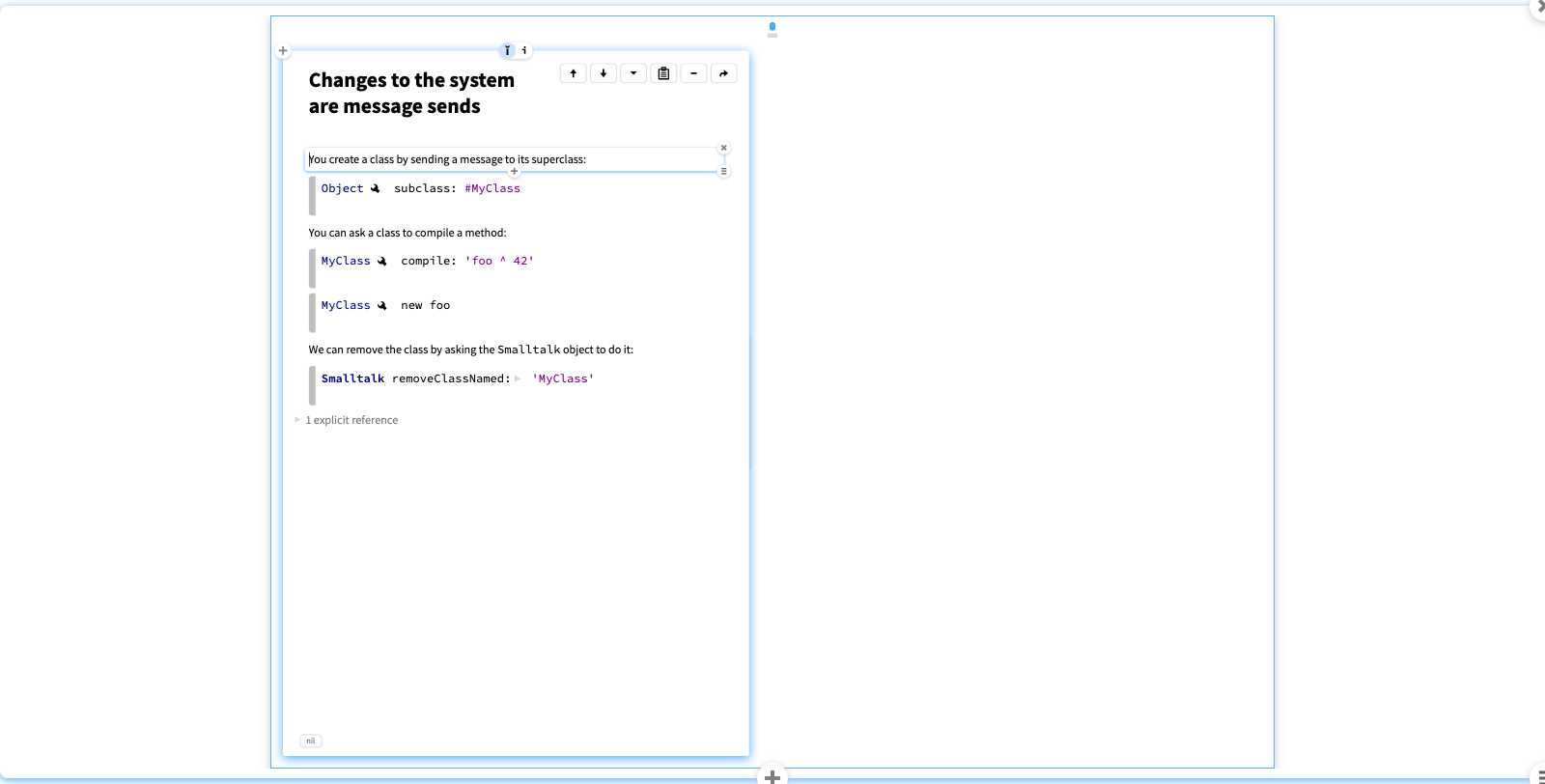

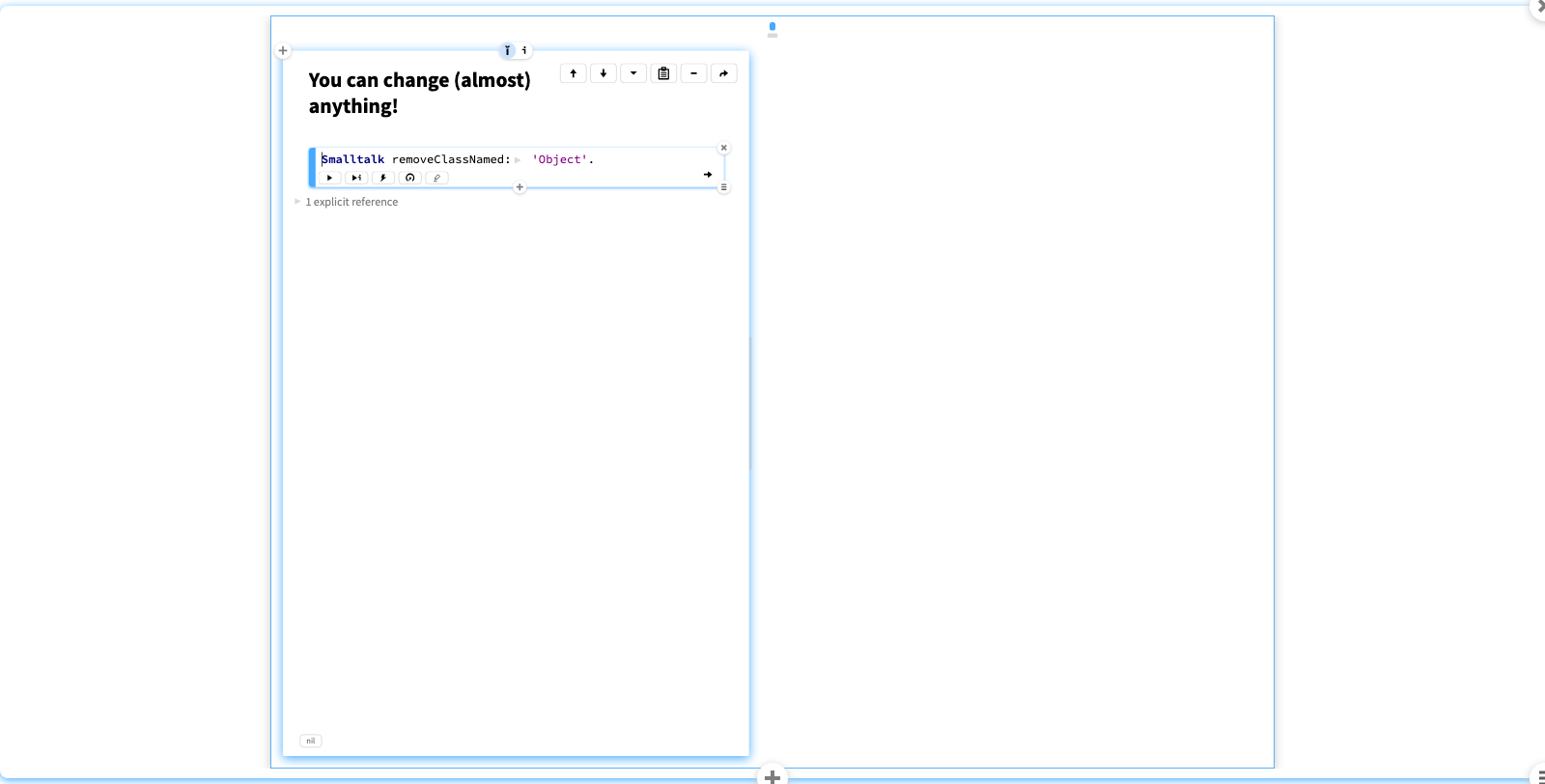

Changes to the system are message sends

You create a class by sending a message to its superclass.

To create a method, you send a message to the class.

You can also ask Smalltalk to remove a class from the system.

You can change (almost) anything!

Smalltalk is designed so that you can change anything in the system. The consequence is that you are also allowed to shoot yourself in the foot.

Luckily Smalltalk prevents you from removing the class Object, but you can still shoot yourself in the foot in many other ways!

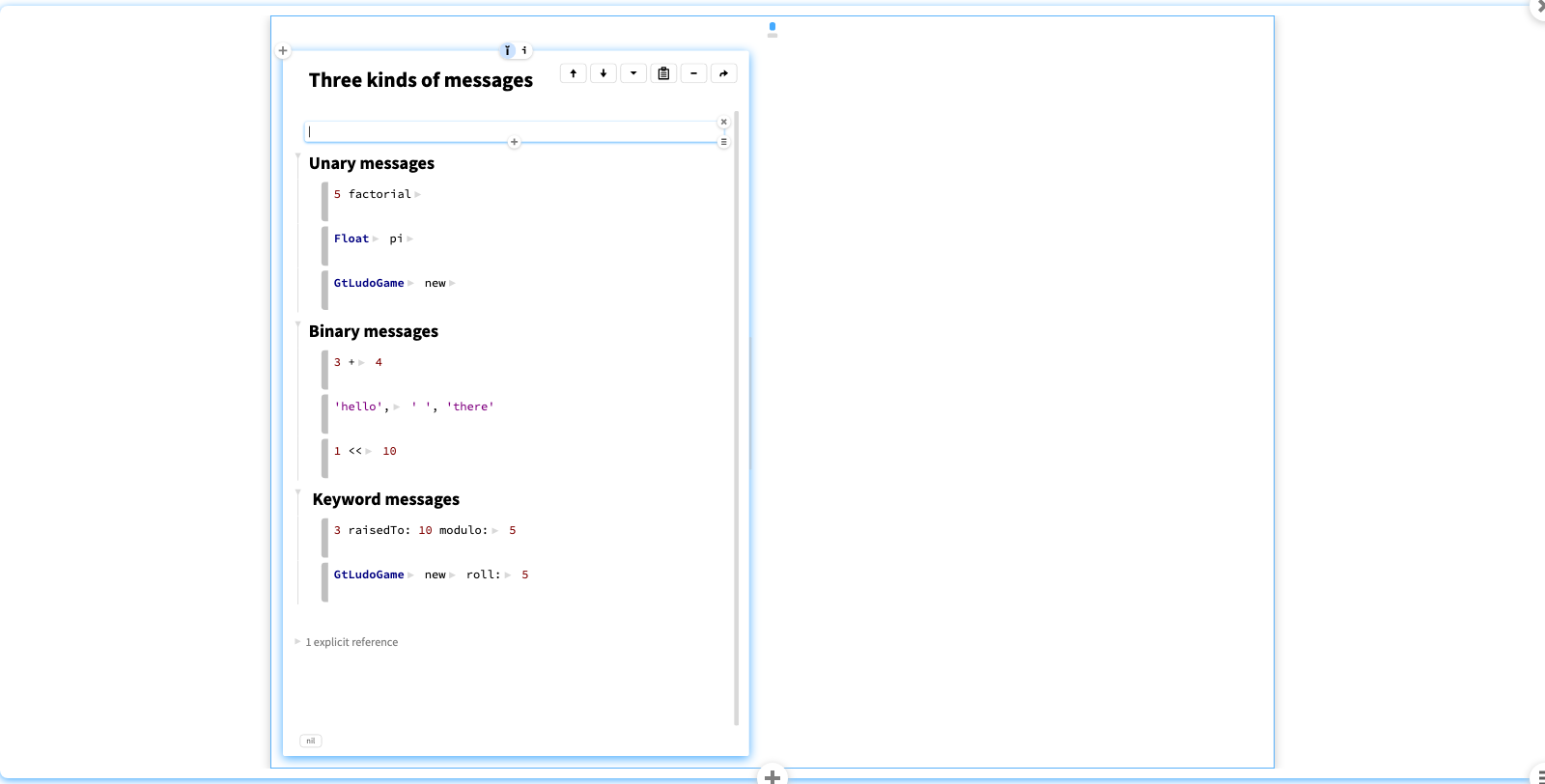

Three kinds of messages

There are three kinds of messages you can send to a Smalltalk object, each taking a different number of arguments.

The receiver is the object to which the message is sent. The sender is the method sending the message (if the code is in a method somewhere). The selector is the name of the message (without the arguments).

Unary

messages have no argument.

5 factorial is a unary message with selector #factorial sent to the receiver 5.

Float pi is a unary message #pi sent to the class Float.

You can also send unary messages to classes, as they are objects too.

Binary

messages are made up of operator symbols like + - * / > < = and others.

They take exactly one argument.

3 + 4 is the message #+ send to the receiver 3 with argument 4.

Keyword

messages take one or more arguments.

Each argument is preceded by a keyword, which ends with a colon (:).

Here the receiver is 3, the message is raisedTo: 10 modulo: 5, and the selector is #raisedTo:modulo:

The Ludo game also accepts various keyword messages.

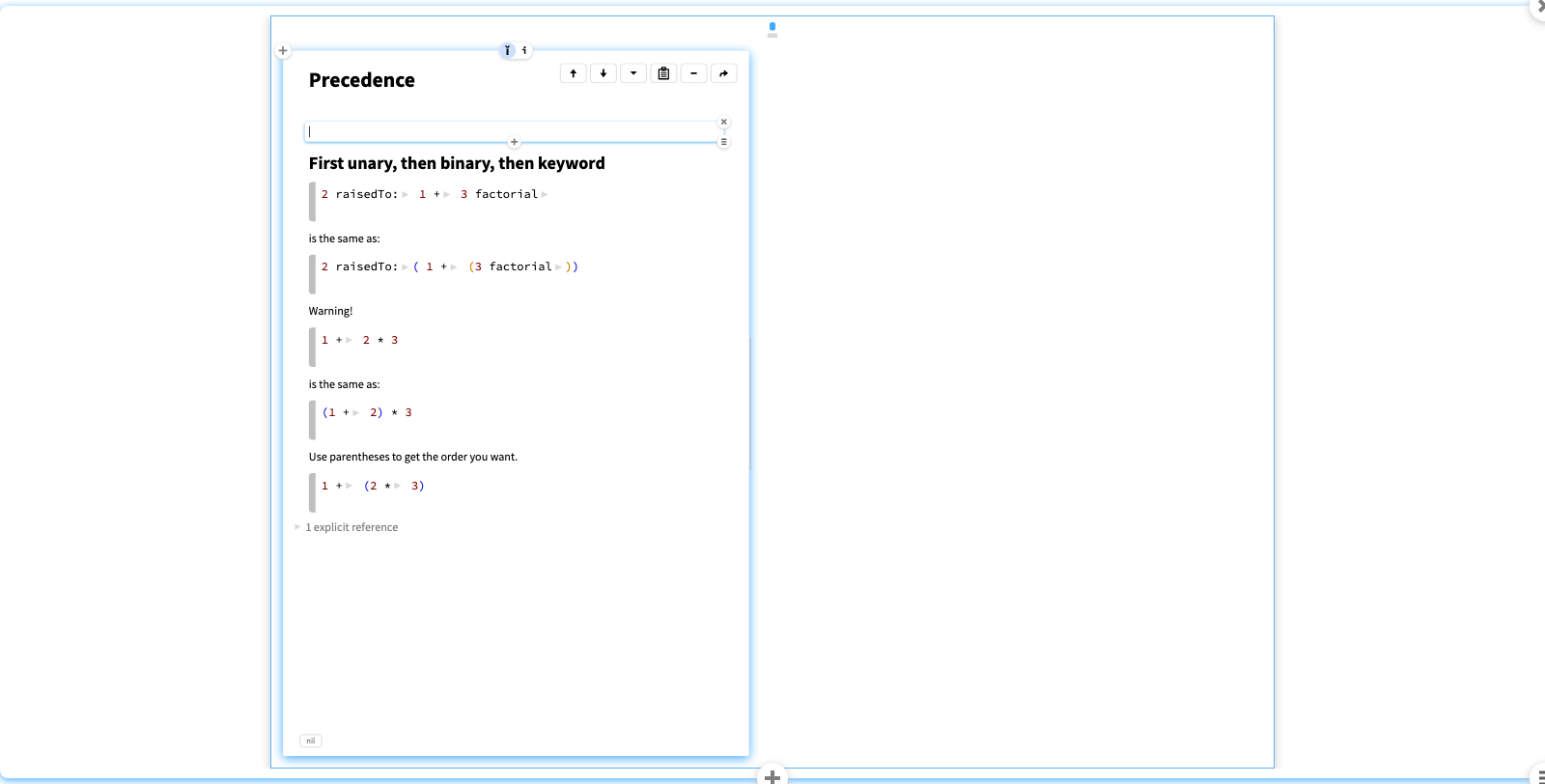

Precedence

In expressions that mix different kinds of message sends, first unary, then binary, and finally keyword messages are evaluated. Otherwise evaluation is strictly from left to right.

The left-to-right rule applies also to binary messages, so 1+2*3 is 9 and not 7.

In practice this is rarely an issue. Just use parentheses to get the order you want.

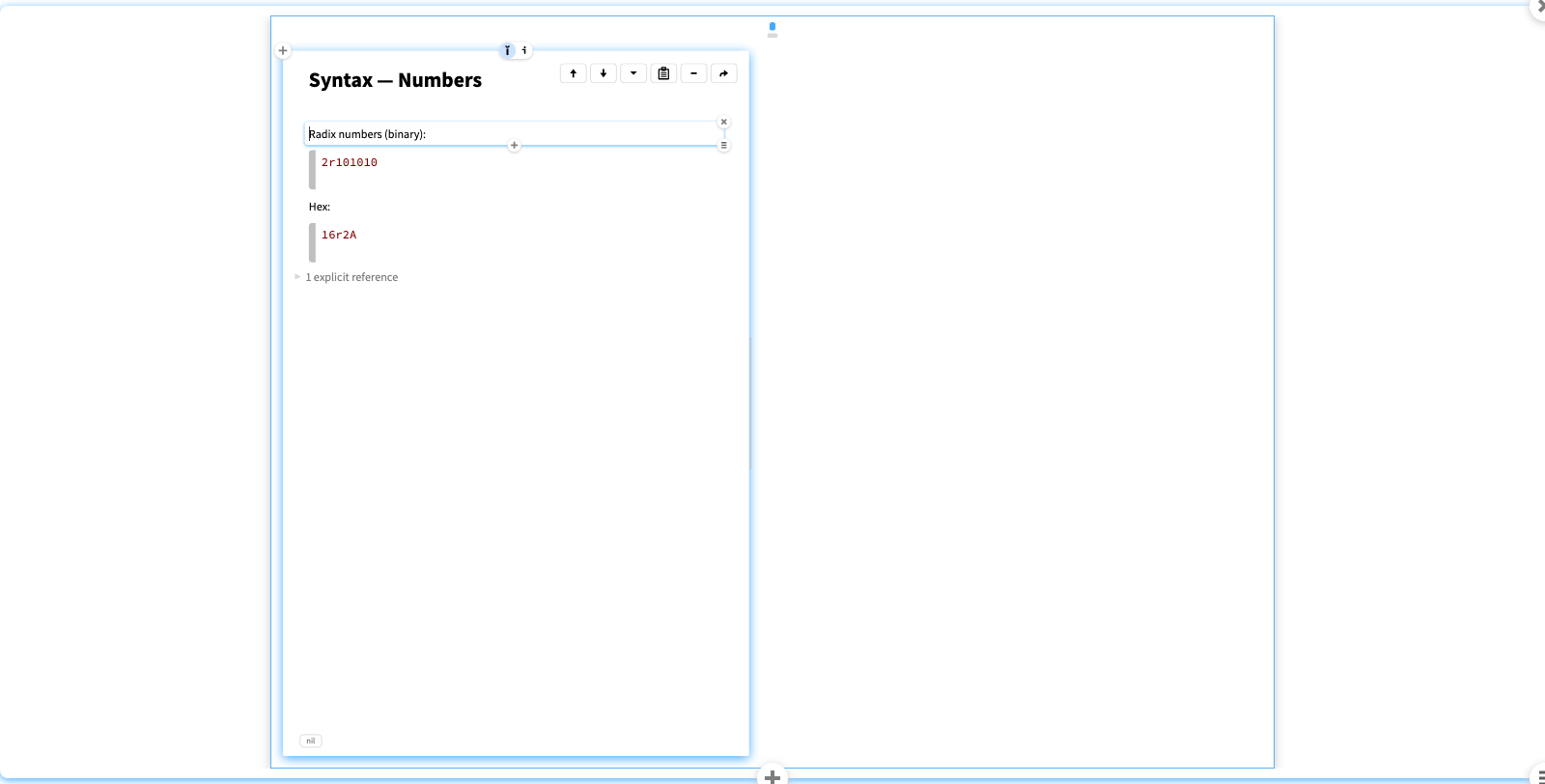

Syntax — Numbers

Smalltalk has a tiny syntax, but there are some interesting differences with other languages.

In addition to the usual integer and floating point numbers, there are also radix numbers, for example this is a binary representation: 2r101010

And this is hex: 16r2A

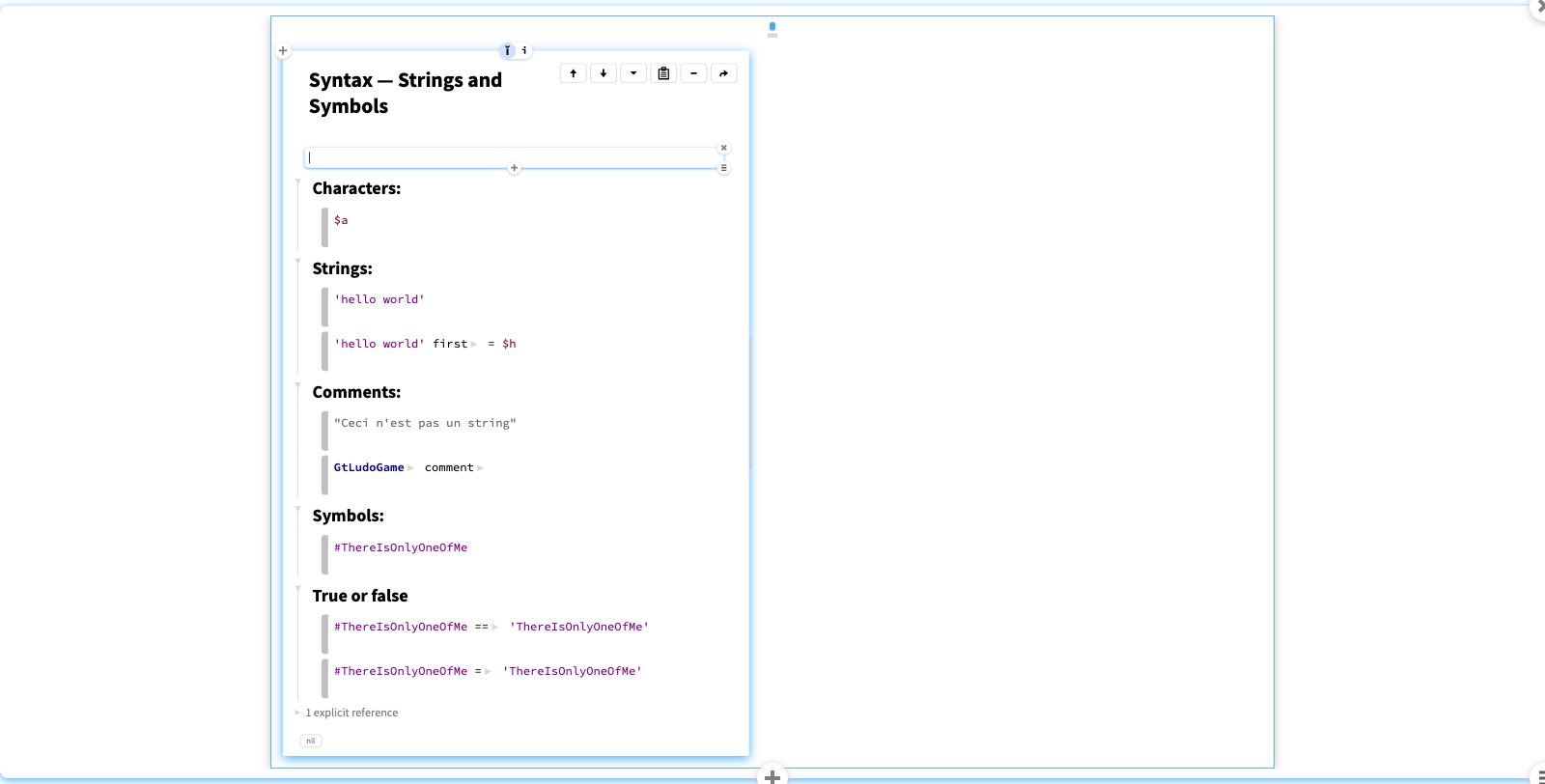

Syntax — Strings and Symbols

Printable characters start with a $.

Strings use

single quotes

.

NB: Double quotes enclose comments, not strings. A comment is not an object, but you can ask a class for its comment and get a string back ...

A

symbol

starts with a hash (#). It is like a string, but has a unique instance.

A symbol is not identical to a string with the same characters, but they are considered equal as values.

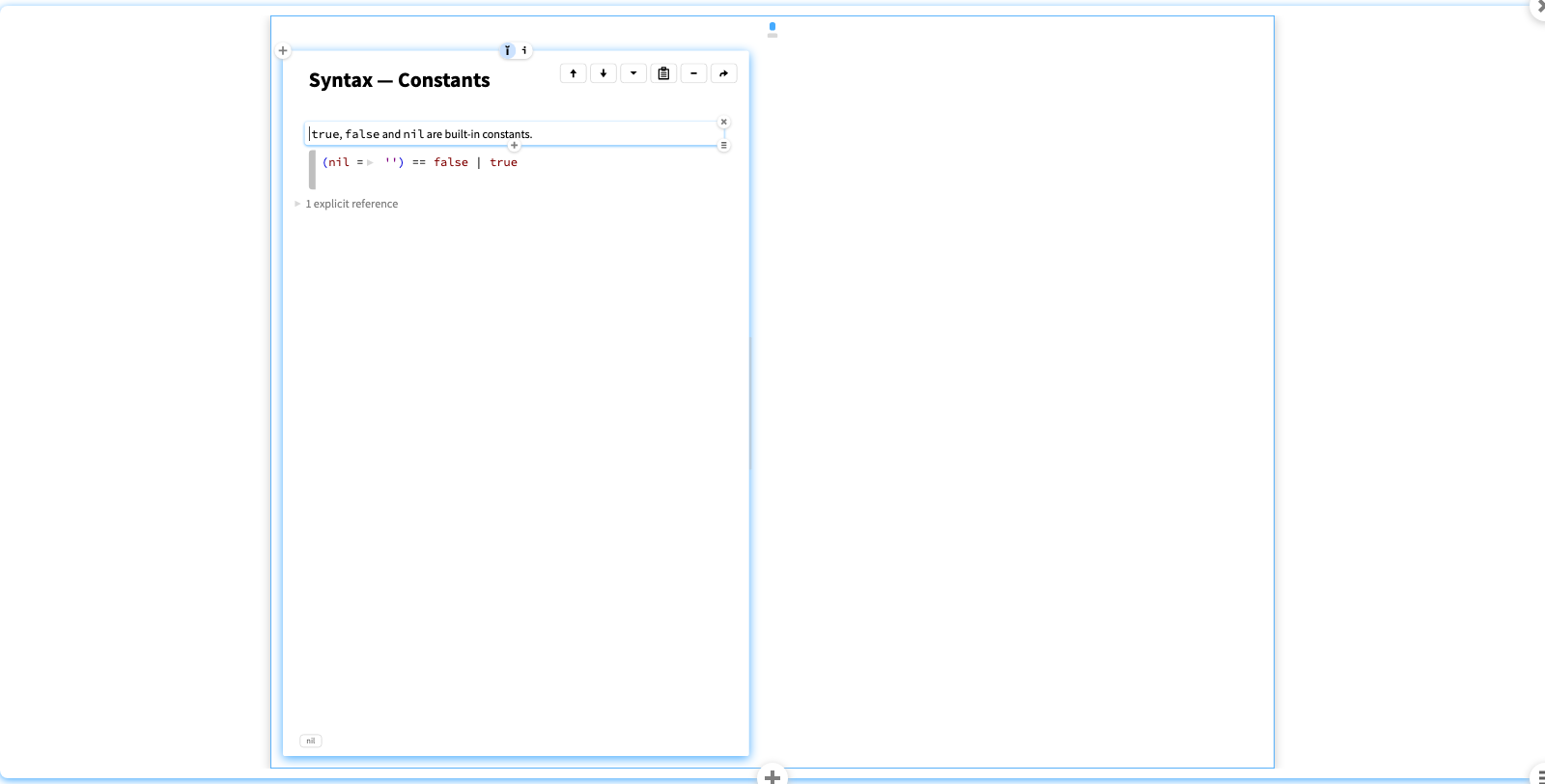

Syntax — constants

There are only 6 keywords in Smalltalk, and three of them are the constants nil, true and false.

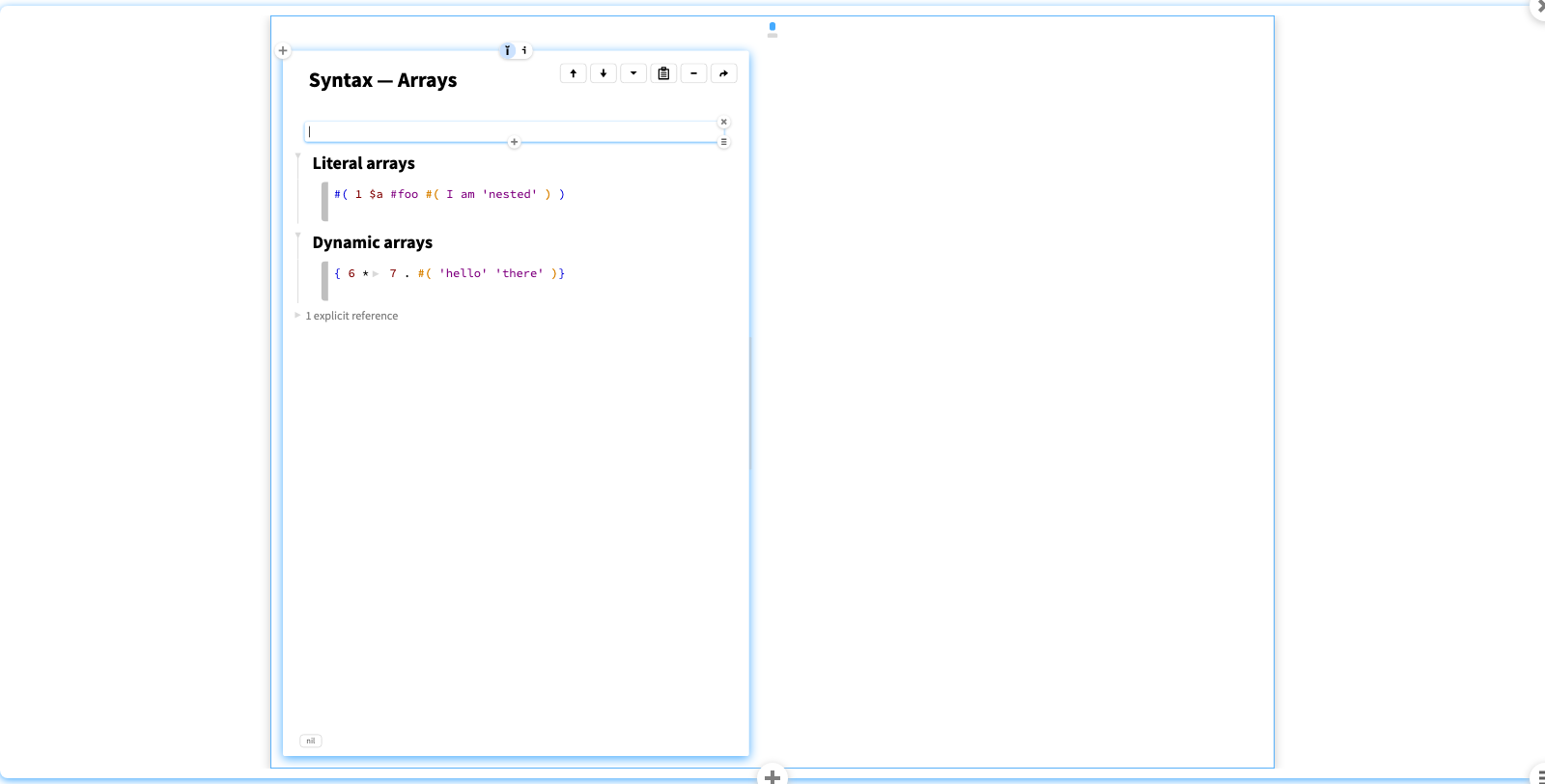

Syntax — arrays

A literal array is a compile-time sequence of literal values. It is specified by a hash followed by possibly nested literal values in parentheses.

A dynamic array is specified by curly braces around a series of expressions separated by periods.

You can embed literal arrays within dynamic arrays, but not the other way around.

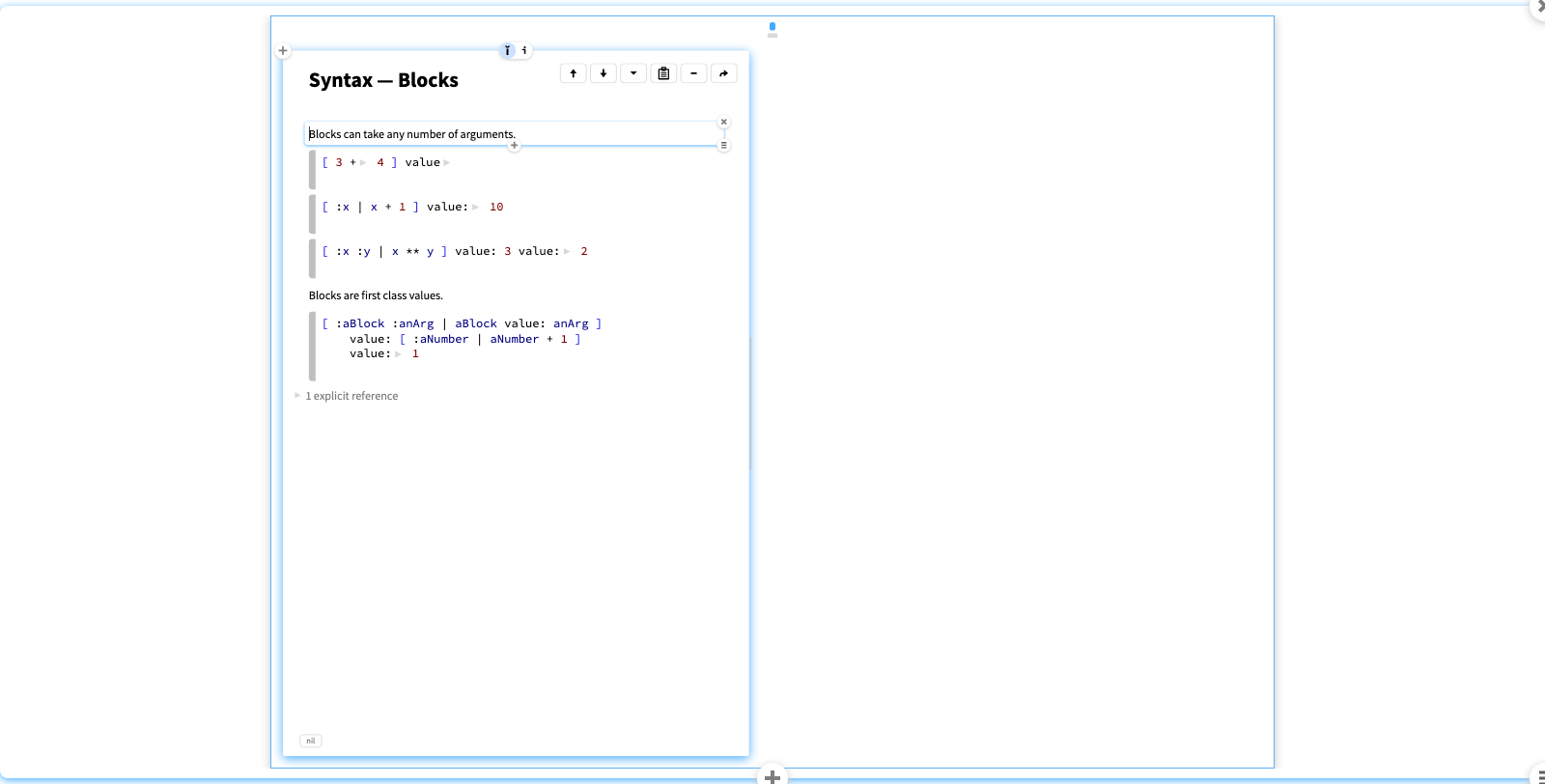

Syntax — Blocks

A

block

is an anonymous function, that can take arguments.

You evaluate a block by sending it the unary message value, or a keyword message value: for as many arguments as you need.

Blocks are first class values, so you can pass them around like any other object. In this example we send a block that increments its argument in as an argument to another block.

Syntax — Pseudo variables

Two further keywords are the pseudo variables self and super.

Both refer to the receiver of a message, but with different method lookup, as in other object-oriented languages.

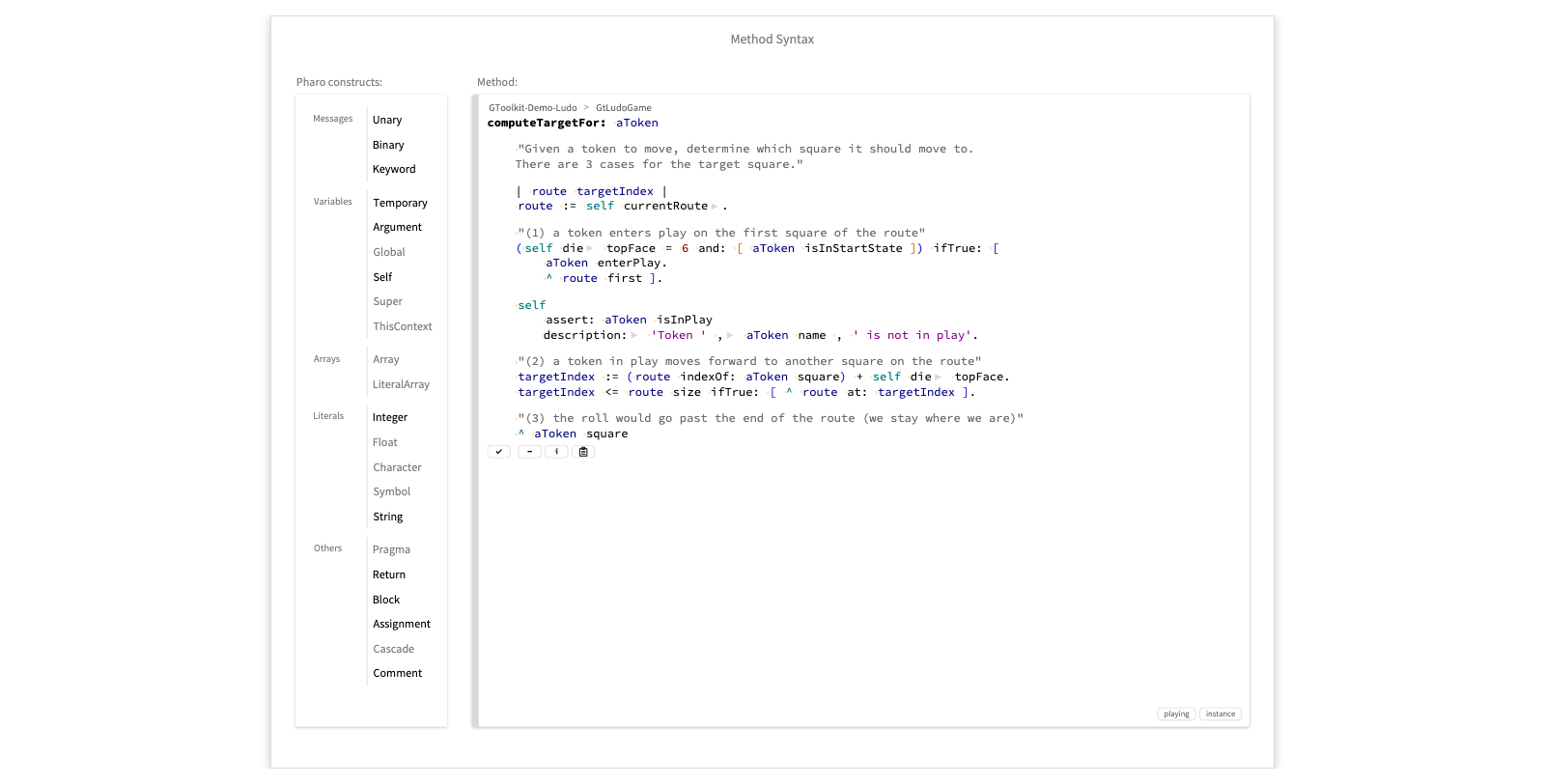

Method syntax

Note the special syntax for variable declarations (|...|), statement separators (period) and returns (^).

Methods start with a declaration of the message selector and arguments. Temporaries must be declared. Statements are separated by periods.

The caret (^) is special syntax for returning a result.

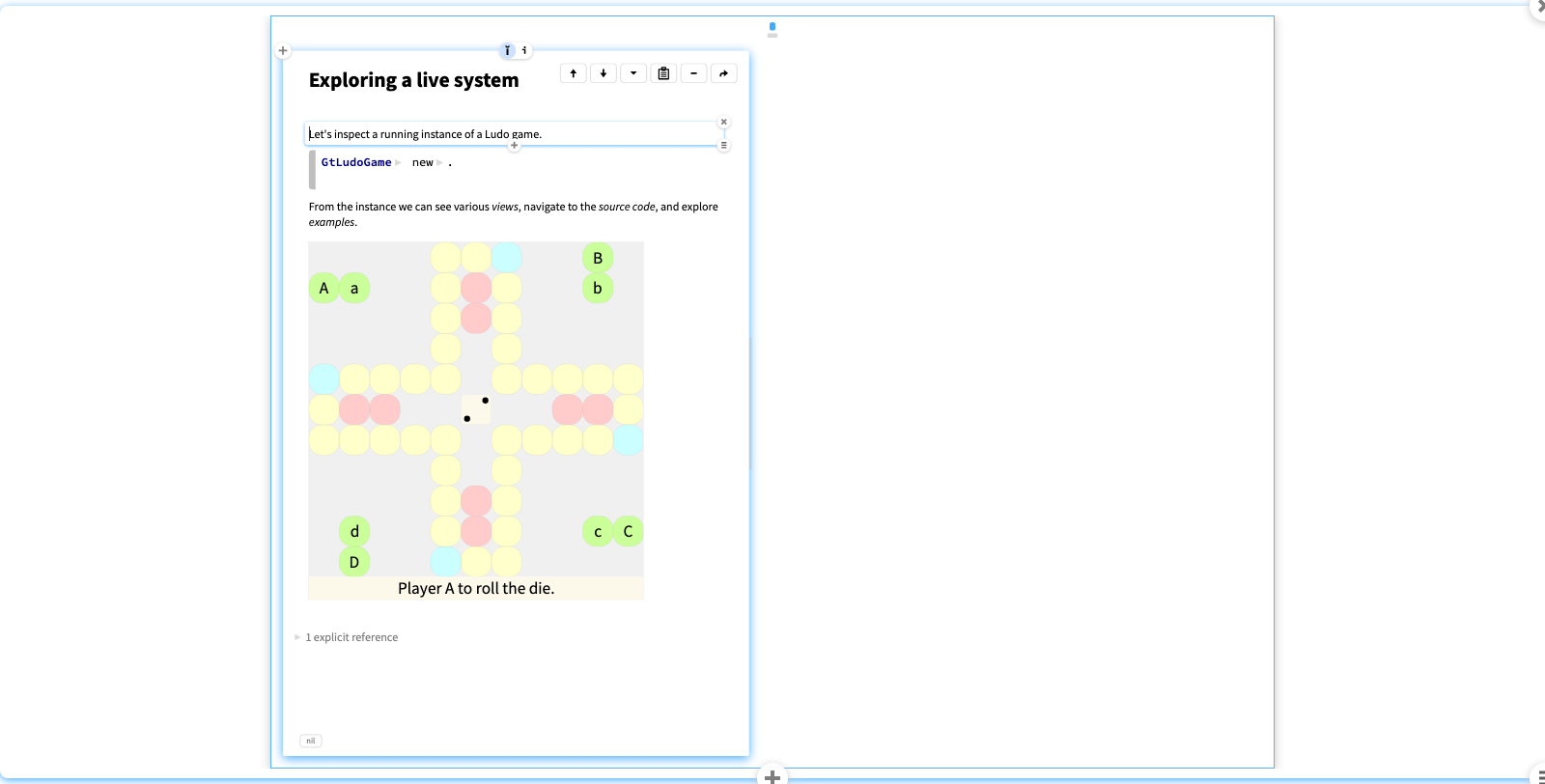

Exploring a live system

Let's inspect a running instance of a Ludo game.

Views

Have a look at the various views (tabs).

The Raw view is the one most IDEs will show you.

The others are specialized views. The Board, Players and Squares views are custom-made for the Ludo game.

Note how you can more easily navigate through the game entites (Players, Tokens, Squares) using the dedicated views than with the Raw view.

You can OPT-click on the tabs to see the code creating each view. Most of these are quite simple. The Board view is the most complex one.

Exploring examples

From the Meta tab you can explore not only the class definition and the source code of methods, but also find references. This leads us to the classes that define test examples.

Let's explore GtLudoGameExamples

.

From the Examples view we can run all the tests.

Let's have a closer look at GtLudoGameExamples>>#playerAentersTokenA

.

It's a simple scenario of a token entering the game after a 6 is rolled.

Note that we can inspect and interact with the example that results from the test, and we can use the example to build further tests. (We'll look more into this in a moment.)

If we open a second view of the same object — just click on the (i) (Inspect Object) button at the top right — we see that they stay in sync.

You can interact both through the GUI or programatically and the views will stay in sync.

- Inspect the game.

- Show the Raw view, then the others.

- OPT-click tio show the code.

- From the Meta tab find the refences to GtLudoGameExamples

- Explore playerAentersAndLandsOnA -- show how it composed.

- Inspect the example and a second copy.

- Evaluate the code: game die roll: 5. and game moveTokenNamed: 'A'.

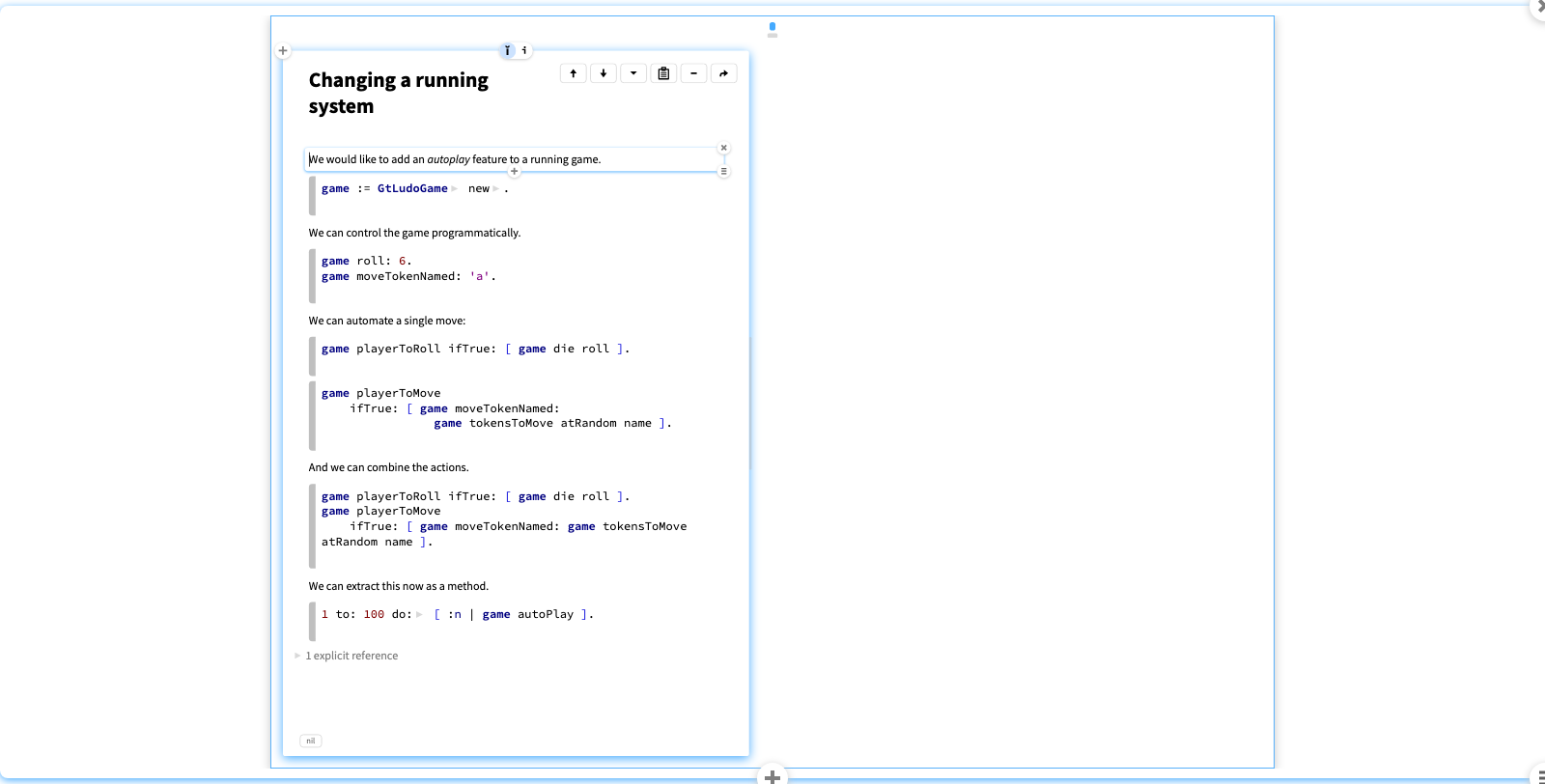

Changing a running system

Since games may last a long time, an autoplay feature would be useful to exercise the game. We start by inspecting a live instance.

We can interact with it programatically. (NB: Just evaluate the snippet instead of inspecting the result, to see the effect on the game.)

By exploring the

testing

protocol, we see that the methods GtLudoGame>>#playerToRoll

and GtLudoGame>>#playerToMove

tell us what should happen next.

Also GtLudoGame>>#tokensToMove

computes the set of tokens that can possibly move next.

We roll the die or move as required.

We can extract this as an autoplay method.

If we run the autoPlay method to the end, we get an error.

We add a test to do nothing if the game is over.

- Inspect the instance.

- Introduce and execute the snippets.

- Extract the autoplay method.

- See that an error is raised at the end.

- Add the line: self isOver ifTrue: [ ^ self ].

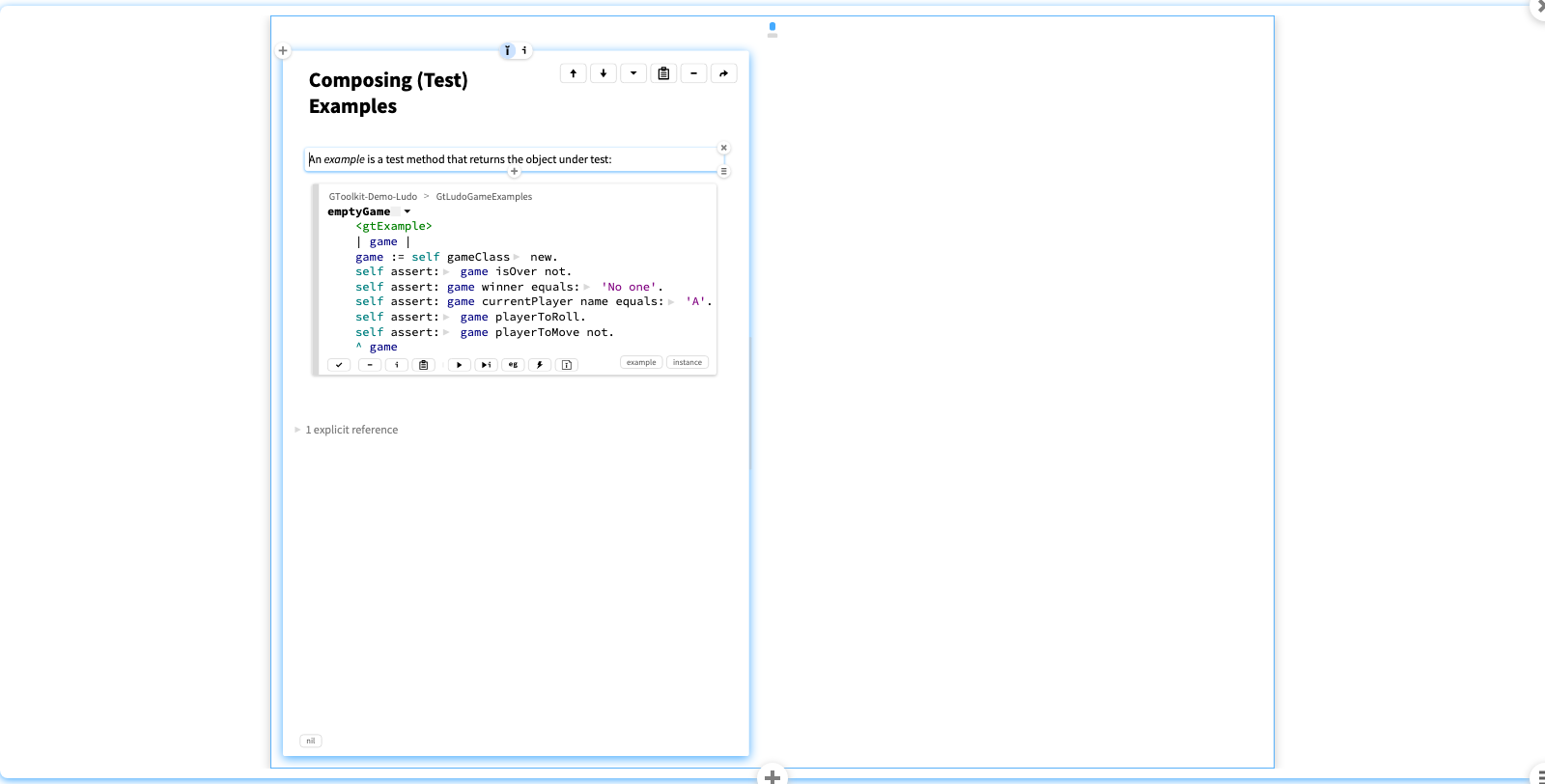

Composing (Test) Examples

In GT, unit tests are written as example methods .

An example method is just like an ordinary test method that we know from the Xunit frameworks, except that an example method returns an instance of the tested object .

This is useful for many reasons, but mainly these two:

1. Instead of just ending with a passed (or failed) test, you have an object that you can inspect and explore.

2. The resulting example can be used as a starting point for composing further tests.

We see here a simple example method for the Ludo Game.

It's an ordinary method, except that it uses the gtExample pragma (annotation), it has assertions, and

it returns an example

.

If you Play and inspect the method, you will obtain the example to explore.

If we browse the

senders

of the emptyGame method, we see it is used to build another example.

The GtLudoGameExamples>>playerArolls6 method builds on the emptyGame example and exercises the scenario where player A rolls a 6.

The tests cover all the special corner cases of the game. For example, what happens if a players rolls a 6 twice, and the second token lands on the square where there is already the first token?

We split this into two examples. The first sets up the situation where there is already a token for player A on the initial square.

The next example starts from this one, and check what happens when the next token enters play.

From the

Examples

tab of the GtLudoGameExamples class we can both run all the tests, and explore individual examples.

If we select the Examples map view, we see that the test examples form a hierarchy built up from the emptyGame example.

- Change some assertions to see what happens if they fail.

- Browse the senders and explore playerArolls6

- Browse senders of playerArolls6 to find playerAentersTokenA

- Again browse senders to find playerAentersAndLandsOnTokenA

- Navigate to the class of the last method, and maximize the view to show the class coder

- Show the Examples view to run the examples, and the Examples map to show the hierarchy

Recording and visualizing token moves

A shortcoming of the game is that there is no history of the movement of the tokens. We only see snapshots of the board. If we could keep a history of the moves, then we could also visualize the actual transitions.

We design GtLudoRecordingGame

as a subclass of GtLudoGame

that keeps a history of the moves.

This compels us to turn the concept of a

Move

into a first-class object, an instance of GtLudoMove

. This class has the responsibility to track the actual move data (the die roll value, the token moved, and the list of tokens moved as a result).

We subclass our examples, so we now have recording versions of them all.

Let's inspect the GtLudoGameExamples>>#playerAovershootsGoal

example.

Inspecting this still just shows a snapshot, but if we look at the

Moves

tab, have the history of the moves.

More interesting, we can now visualize which tokens moved where by inspecting the individual Moves.

Note in particular the second move, which required two hops.

We can now track all the moves that are played with the autoplay feature. Let's open up two side-side views of a new game, with the second one showing the list of moves.

Now that we have first-class Move objects, we have a complete history of a game. We can also replay all the moves up to a certain point, and go back in time to see the state of the game at any point.

- Inspect the snippet

- Go to the

Moves

view, and inspect individual moves

- Inspect a new recording game, and open a second inspector to the

Moves

view

- Evaluate self autoPlay: 1. in the playground to see the updates

- Select a move and play the

Replay to here

action

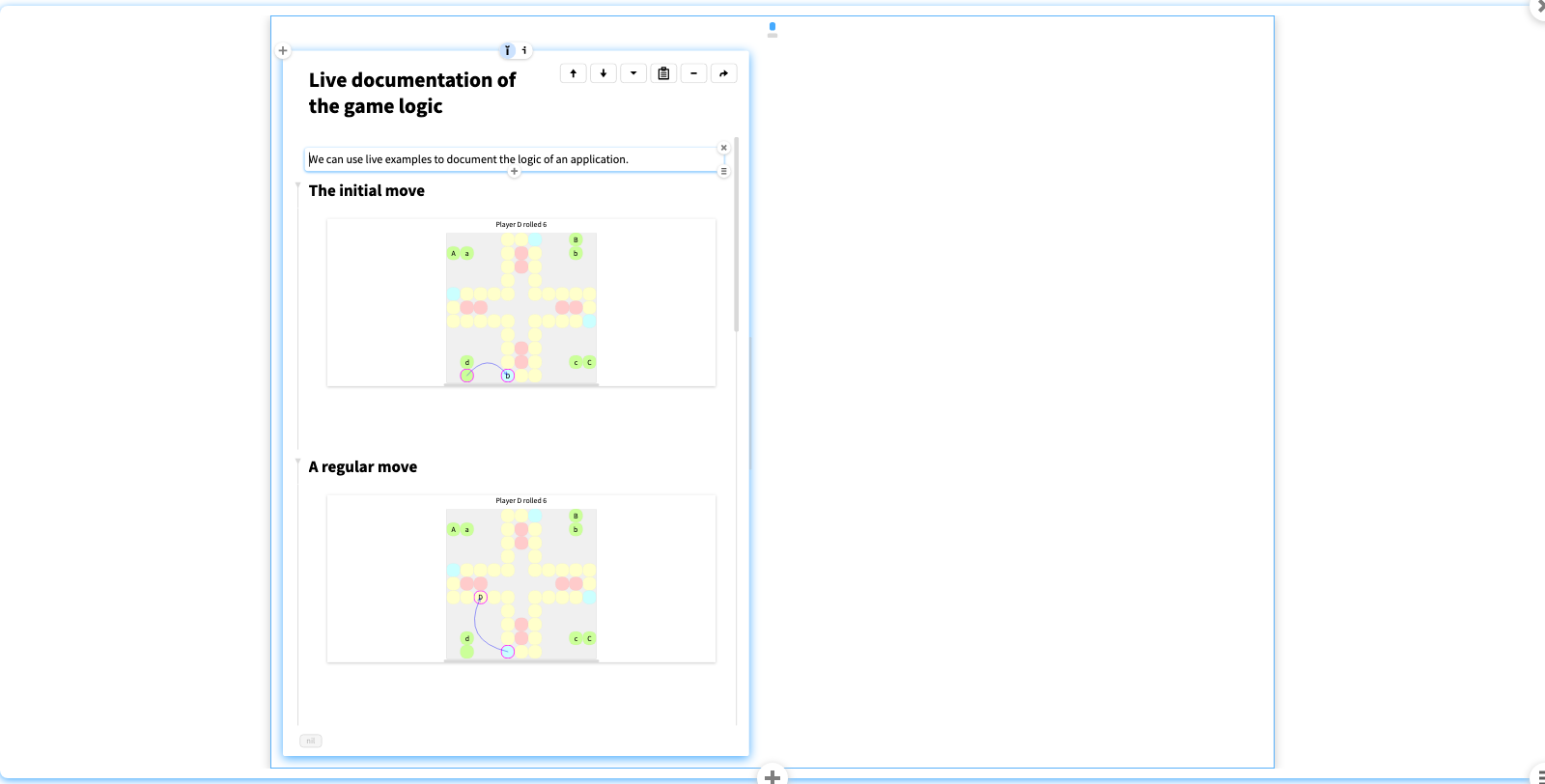

Live documentation of the game logic

Notebooks (such as this one) can serve as live documentation for the logic of the game (i.e., the business domain ) as well as for the technical solution.

Consider the example game GtLudoRecordingGameExamples>>#gameShowingAllMoves6

, which shows a short, complete game.

The examples can then be embedded into the notebook to form live documentation of the different cases of moves.

Show and explore the impossible move.

Live documentation of the technical solution

We can generate live diagrams from the source code. A UML diagram showing all the details is rather cluttered and nit so useful.

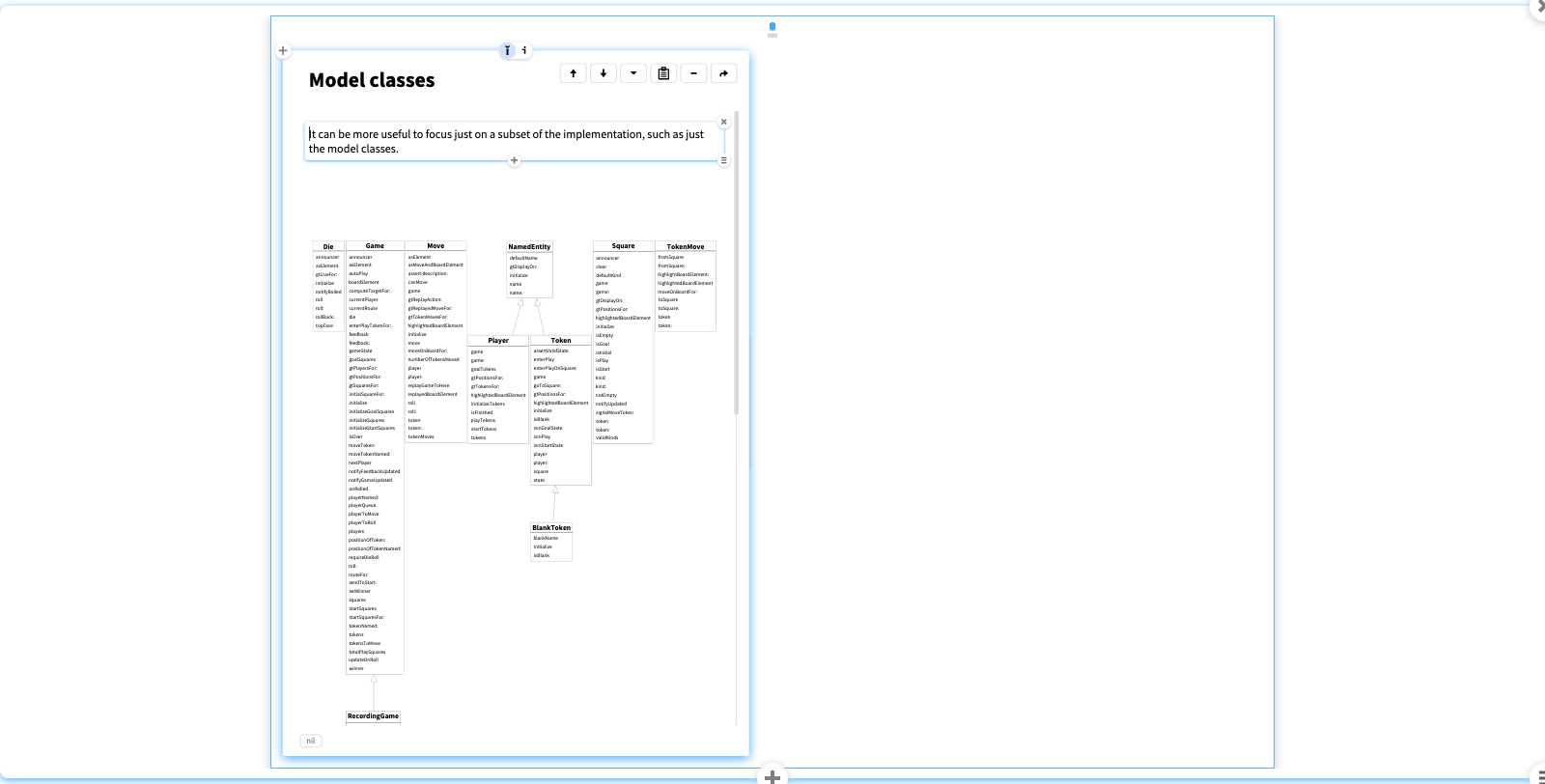

Model classes

If we just focus on the model classes, we get a better view, but it still contains more details than are useful.

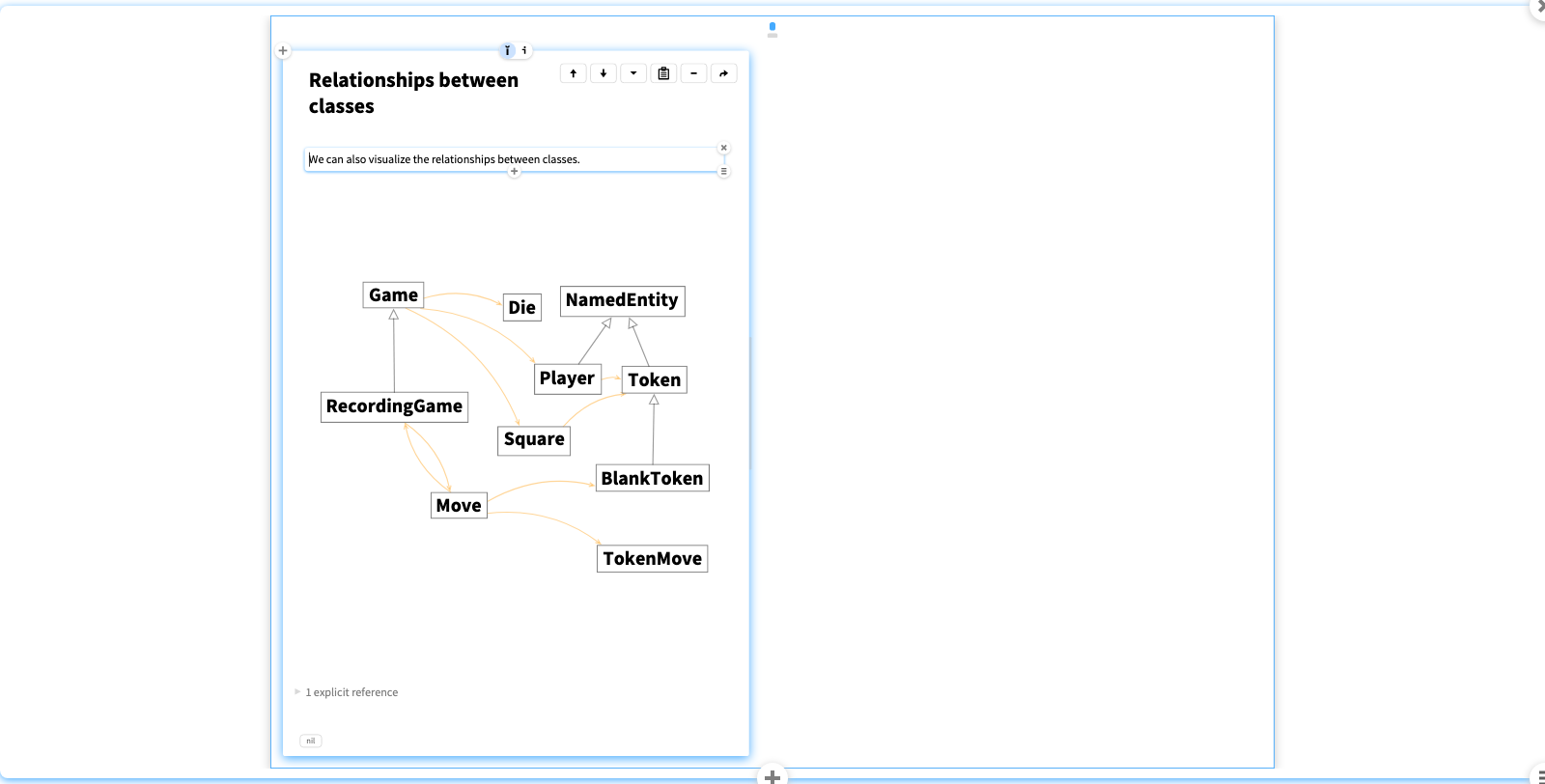

Relationships between classes

Instead a class diagram just showing the key inheritance and usage relationships gives us more insight into the design.

A particular advantage is that such generated diagrams are live and integrated with the other tools.

Show that the diagram is live, and that we can navigate to the code and examples.

Take home messages

Summing up, Smalltalk is one of very few software systems which enables fully live programming, in which programming means changing a running system.

We have also see how live examples extend conventional unit tests to yield explorable objects that can not only be composed to form hierarchies of tests, but they can also be used to form live documentation.

Finally the ability to mold the development tools to the needs to the application being developed allows you create fully explorable and explainable applications.

What's next?

The Glamorous Toolkit is an open-source system that runs under Linux, Mac and Windows. All the examples we have seen, as well as this slideshow are part of the download.

There is also a lively community around Smalltalk, Pharo and GT. I encourage you to try it out and explore.